The Adventures of Mark Twain (1944) features a central figure so familiar as to be legendary, and the film

leans heavy on legend. We mark

tomorrow’s anniversary of Mark Twain’s birth.

What we discover about Mark Twain through this movie is not

so much facts about his life (particularly when the facts are toyed with and

not in the order of their appearance), but rather how he fits into, and even represents, the grand

mosaic of 19th century American culture. This is a rich story of a vibrant era.

We are also treated to the rarely-presented world of history

through literature.

Bret Harte, William Dean Howells, Longfellow, Whittier,

Emerson, Rudyard Kipling all parade before us.

They are cameos, but they are presented as giants. I particularly like that the film expects us

to know who they are.

A modern film might throw the answers to an ignorant

audience the way a fellow student slips test answers to a pal beside him,

which is ignominious, and unflattering both to ourselves and the great writers.

Mark Twain’s greatest struggle, apart from money worries, is

to measure up to these literary lions.

That he finds his own place in popular literature and that the 20th

century lauds him with movies and stage plays and television programs, and does

not do so for the aforementioned first-string players — this would astonish

Twain more than anyone.

This is a film more of style than of substance, and for

those dismissive of it I would suggest they consider that in classic film, a

biopic is less like a Ken Burns documentary and more like an interpretive

dance.

Yes, I am being facetious.

The movie is a series of events like tall tales, and even

the introduction to the film cheekily warns us not to be too judgmental. First we are on a hill watching Halley’sComet awe and terrify the townspeople as Samuel Langhorne Clemens is born into

this world. He will joke repeatedly

throughout his life that he came in with the comet and will surely leave the

earth when the comet is due to return in the next century. In a life of quips and witticisms, and wry

observations, that he actually did die on the occasion when Halley’s returned

in 1910 is probably the biggest joke of all.

But a lot happened in the meantime, and the movie is stuffed

with scenes that roll out a long carpet of experiences and adventures. The director plunks us down in the 19th

century with beautifully staged settings, many of them artful miniatures, of

the majestic Mississippi, its riverbanks bathed in moonlight. We see the long gambling salon on the

riverboat (too long to be realistic, but this isn’t a documentary, it’s a

pop-up book), and the lordly riverboats that young Sam so admires.

We know he took his eventual pen name, “Mark Twain” from the

call of the riverboat men who are testing the depths of the water for channels

deep enough for the riverboats to pass safely.

Two fathoms is a safe depth, so when they mark “twain” on the measure,

it is two fathoms. The sing-song call, “MARR-R-K…T-W-A-A-A-I-I-N-N!”

is used stirringly at dramatic moments, and is replicated in notes on the

musical score of the film, a clever reprise.

Unlike most movies about great men, Mark Twain is not shown

as a man born to greatness. On the

contrary, he’s a stumblebum who runs off to join a riverboat crew because he

can’t stand working in his brother’s print shop setting type by hand. (His aversion will later move him to invest, disastrously,

in an early mechanical typesetter.) He

runs off to the western mining camps to get rich, and doesn’t. He delivers a stand-up routine at a dinner

for the aforementioned literary giants, and, trying too hard to be funny,

insults them in a kind of Friar’s roast.

His act tanks and we see his panic as he makes a fool of himself. We begin to wonder if this guy will ever do

anything right.

His one stroke of luck seems to be catching a glimpse of a

fellow traveler’s photo of a beloved sister.

Twain falls in the love with the picture, and eventually the woman, who

as his wife will help him achieve lasting success as a writer.

Twain has a lower estimation of his talents, and wants to

write something great and important, but the audience sees, even if Twain does

not, that the body of his work adds up to a chronicling of America in its most

expansive, confident, chest-thumping and stumblebum charm.

Fredric March, who we last saw here in I Married a Witch (1942), is the adult Mark Twain, in a spot-on

performance. It can’t be easy creating a

character so well known, and relying in good part on mimicry and

imitation. It’s a tightrope to

walk. With the help of makeup man Perc

Westmore, Mr. March is the very image of Mark Twain. One of the fine achievements of this movie is

the way the characters, Twain in particular, age so gradually and so

realistically we may feel amazed by the end of the film that so much time has

passed. The aging of characters in other

films of this era is usually something of a jolt, and artificial-looking.

Alexis Smith plays his wife, and though we may note it’s

another woman-behind-the-great-man role where she has little challenge, it’s

still a nice piece for her. This is a

much softer role in contrast to the sophisticates she often played, and with

little makeup in the early scenes, her natural beauty is quite lovely, more stunning

than her glamour roles.

Miss Smith is a one-woman cheerleading squad for Mark Twain,

but in real life Mrs. Clemens did more than just encourage him. She actually edited most of his work and he

came to rely on her judgment.

Alan Hale is along for the ride as Twain’s prospector pal in

his patented jovial scamp gig. John

Carradine gets a marvelous brief scene as the writer Bret Harte who, in the

famed contest between the jumping frogs, exhorts his frog, “Daniel Webster”

with the plea, “If you love me…” And

repeated calls, “Flies! Flies!” to

encourage the magnificent amphibian to hop.

I don’t know if Mr. Carradine ever played a scene so intense with a

human.

Donald Crisp is at Twain’s elbow as his manager, who also

gets the impressive aging treatment. Walter

Hampden is great as Alexis Smith’s disapproving father in a scene where he tries

to remove Twain from his home.

C. Aubrey Smith delivers a magnificent address at the end of

the film when Mark Twain is honored at Oxford.

His scene is a standout. That

beautifully craggy face and his meticulous speech.

Joyce Reynolds, who we last saw here in The Constant Nymph (1943), plays Twain’s daughter, Clara, horrified at spotting the return of

Halley’s Comet.

A few scenes of note:

I love when the teenaged Samuel Clemens is getting his first lesson in

piloting a riverboat by grumpy Robert Barrat.

Dickie Jones is the youth, who has very few lines, but the scene is

marvelous. It runs quite a long time,

with close-ups on the boy’s face as he nervously reacts to the dangers of the

river and Mr. Barrat’s constant barking at him.

He’s shaking in his shoes, and when at last he manages to

pull into a safe channel and the crewman sings,

“M-A-A-R-R-RK…T-W-A-A-I-I-N-N-N!” we see the tears glisten in his dark velvet

eyes with wonder and gratitude, and love of this river. I don’t suppose it’s necessary to the story

as a whole, but I imagine director Irving Rapper kept the attention focused on

Dickie Jones for so long because he fell in love with the boy like I did. I think it’s one of the most powerful close-ups

I’ve ever seen.

The anxious expression in his soft boy’s face, on the verge

of manhood. We last saw Dickie as a much

younger child here in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) where he played the

congressional page.

The scene where Mark Twain does one of his very first public

speaking jobs. Look at the hall filled

with extras, and look at their costumes.

Such attention to the style and setting of an era is wonderful. There don’t seem to be many shortcuts taken,

as we sometimes see in other films where the sets or costumes, or hair is

judged by the studio evidently as being “close enough.”

We may gag at Twain’s grotesque, “well done, good and

faithful servant” joke, and note how African Americans, particularly the

unfortunate Willie Best as a butler, get the stereotypical treatment in this

film. However, there is an aspect to their

presence in this movie that I admire, and that is that they are indeed

present. We see them on hill watching

Halley’s Comet, and as passengers on the riverboat. They work on the river, and live on the

river, and they are the boys on the raft.

If their story is not told yet, at least we see they are not

invisible. We see they are part of the

mosaic that makes up America. For

Hollywood at this time, this is something.

We get a glimpse of Mark Twain’s house in Hartford. See my post on my New England Travels blog for more on his home, which still stands a museum today. This weekend, another actor famed for

portraying Mark Twain, Hal Holbrook, will be honored at the Mark Twain House when a hall is dedicated in his name.

As Mark Twain’s life unfolds it gets busier. He and his wife lose a baby son. They have three daughters. He travels the world to earn money to pay

back debts. He saves the fortunes of Ulysses

S. Grant when the former Union general and President is dying of cancer, and

struggles to write his memoirs to provide for his family. Twain, in his own fledgling company,

publishes them.

March has a moving scene when he sings “Swing Low, Sweet

Chariot” at the piano as his wife lay dying.

Decades later in an interview Alexis Smith noted that Fredric March’s

work in this movie was underrated. In an

article at the time of filming, she commented that she had a hard time, even

though she was supposed to be dead, to keep from peeking at March to watch him

in his scene.

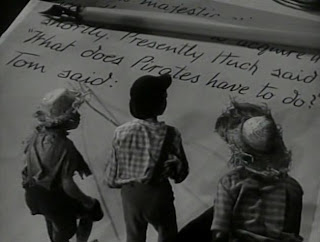

Back to the pop-up book nature of the movie — the scenes

where tiny figures of Huck Finn, Tom Sawyer, and Jim superimposed on the

written page, or revisit Twain at the moment of his death and take him by the

hand to a distant sunset are imagery we would not see in a biopic today.

But this is a tale, not a documentary. It captures the mood and the tragedy, and

optimism of this man’s era. We may be

witnessing more Currier and Ives than Vital Records, but that is the nature of

interpretive dance.

Remember also that during World War II the movies were

reaching back to a comfortable American image to appeal to a frightened

audience. Twain’s speech, “our tolerance

will never become indifference, and our freedom never come license. Let’s respect each other’s rights…” reflects

not only his progressive views, as cantankerously as he sometimes phrased them,

but also speaks to a nervous America on the precipice of doom.

For more on The Adventures of Mark Twain have a look at

Cliff Aliperti’s two posts on his terrific Immortal Ephemera blog here and

here. The movie was filmed in 1942, but

not released until 1944. For a more

detailed explanation why, have a look at Harold Sherman’s “Behind theScreenplay” here.

*********

Jacqueline T. Lynch is the author of Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. and Memories in Our Time - Hollywood Mirrors and Mimics the Twentieth Century.

10 comments:

I enjoyed this look at a movie I've not yet seen. As an Alexis Smith fan I definitely plan to catch up with it. :)

It's kind of fun that Twain was part of New England yet also part of the west -- I have a book about his travels through the Sierras, where his stops were said to have included places familiar to me such as Bridgeport and Mono Lake.

And then he's also a part of one of the iconic spots in Disneyland, LOL, the Mark Twain paddlewheeler which has been operating since Opening Day back in July 1955.

Best wishes,

Laura

Thank, Laura. Truly, Mr. Twain belongs to us all.

This is just perfect: "this isn’t a documentary, it’s a pop-up book." I love how this movie isn't just a mix of fact and fiction but a mix of fact and Twain's fiction.

Thanks so much for linking over.

I think I enjoyed your thoughts on this movie more than the film itself, which means it might be time for me to watch again--thanks for pointing me back to it!

Thank you so much, Cliff. I really enjoyed your posts on this movie earlier in the year. It's a cluttered curio cabinet of a film, and all the more interesting because of it.

A documentary probably would make me tear up at the end. I must take a cue from yourself and Ms. Smith and watch this film soon to admire Mr. March's work.

Lovely article.

Thank you, CW. Hope you can catch it soon.

This sounds pretty interesting, though more for Fredric March. I did a piece on him earlier this year for a blogathon, which made me appreciate his work, especially when I saw 'The Best Years of Our Lives' a month or two back.

Hi, Rich. Fredric March is tops, and "Best Years" is one of my favorites. I can't count how many times I've watched it. Seeing that for the first time is usually an unforgetable experience for classic film fans.

Excellent review- I've never seen this one either, but now plan to rectify that situation. C. Aubrey Smith is one of my favorite character actors- so that's always a plus in a film's column. It's serendipitous for me to read this as I am currently reading a book about Twain and his meeting with the real life Tom Sawyer in San Franscisco who would go on to inspire Twain's literary character. It's called Black Fire by Robert Graysmith, and so far it is quite good. This movie will be a nice bookend to finishing that book.

Cheers-

JC Loophole

Thanks, Mr. Loophole. So nice to hear from you again. I'm with you on C. Aubrey Smith. The book you're reading sounds good.

Post a Comment