Happy New Year! Thank you for the pleasure of your company this past year. See you in 2011.

IMPRISON TRAITOR & CONVICTED FELON TRUMP.

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Monday, December 27, 2010

Off Topic - Children's Books during World War II

This is to pick up the thread of a conversation we began in the comments section of this post a month ago that introduced the series on home front “war stories”. I’ve had another project on the back burner for some time with which some of you might be able to help.

This involves a possible book about children’s books written during World War II, about that war. We’re not talking about any classics of children’s literature here, no Caldecott or Newbery Award winners; what I mean are those series books, the pulp novels that engaged teens and pre-teens with a weird combination of childlike adventure and all-too adult angst about the consequences of not doing one’s patriotic duty during the war.

Some of these were a series featuring the same character, like the “Dave Dawson” books, where he and his pal, Freddie Farmer, fought the enemy pretty much all over the globe. Likewise “Red Randall” who began his teenage trial by fire at Pearl Harbor. Both series were written by R. Sidney Bowen.

“Cherry Ames” went from nursing school into the Army, served in Panama, some non-disclosed islands in the South Pacific, flew through a hailstorm of gunfire over Germany, and finished up her tour of duty as a nurse in a veteran’s hospital. I won’t guess how many girls pursued nursing careers because of this series, but I know there are some out there who admit to it.

Other series followed a theme of wartime service but featured different characters. Whitman Publishing, who practically cornered the market in children’s series books at the time, produced several pulp novels under their “Fighters for Freedom Series”. This gave us “Nancy Dale - Army Nurse”, “Dick Donnelly of the Paratroops”, “Norma Kent of the WACS,” “Sally Scott of the WAVES”. “Kitty Carter of the Canteen Corps” showed us we didn’t necessarily have to be in the military to help the war effort.

The publisher touted these as “Thrilling novels of war and adventure for modern boys and girls.”

It was a tough being a modern boy or girl when war might be all you remembered, and would determine a future you could not imagine, a future which seemed to hang precariously on whether or not you displayed your full measure of devotion and courage. Just eating your vegetables wasn't good enough anymore.

There are several elements to these stories which are quite striking. One is the, in some cases, unsparing description of death and cruelty, and the fatalistic manner in which the tone of these stories seems to indicate the young reader should accept these conditions. Nancy Dale’s troop ship is torpedoed, and she spends several days in a lifeboat with a handful of other nurses and crew members. One dies and they dump the body overboard.

At one point in the story she receives word her brother is missing in action and presumed dead. A family friend, comforting her, tells her not to hold out much hope of his survival. “Don’t let wishful thinking keep you from facing reality, my dear. There’re many things worse than death in this war.” How would a kid, who had relatives in the war, take this message?

On the frontispiece of “Red Randall at Pearl Harbor”, published by Grosset & Dunlap, we are reminded that “This book, while produced under wartime conditions, in full compliance with government regulations for the conservation of paper and other essential materials is completed and unabridged.” Even the book itself has the imprimatur of self sacrifice.

If you find these books today, the pages are yellowed, few of them have book jackets left intact, but many of them have the signatures of the children to whom they belonged. Or, in this case of this flyleaf of “Norma Kent of the WACS” - “To Shirley from Grandma - December 25, 1944”.

What I’d like to know from you is your memories of reading these books, how you discovered them, and what impressions they had upon you. Perhaps you were, like Shirley, a child at Christmas. Perhaps you were Shirley’s younger sister or brother, getting her hand-me-down books five or ten years later, when the aftermath of the war was known and the wartime service remained a badge of honor out of reach for this first succeeding generation. Maybe you were her daughter, or grandson, and found these books in an attic. You could have read them when the war was current events, or something that came alive for you one rainy afternoon in the 1970s.

I’d like to know about that particular American generation, who became adults in the early 1950s, perhaps still “shell shocked” by a childhood of vicarious victory and defeat, who found themselves taking places of responsibility in a society where, though regimented, not everyone played by the rules.

I’d like to hear from the all the nurses, the sailors, the fliers, who became what they did because of a book they’d read when they were fourteen.

I’d like to hear from the romantic nostalgic buffs who learned history from flea market artifacts like a written-to-formula kid’s novel about a world turned terrible where the monsters were real, and you never read “and they lived happily ever after” at the end.

If you have any thoughts to contribute, please email me at: JacquelineTLynch@gmail.com, with the understanding that any communication might be used for possible publication, though all requests for anonymity will be honored. No email communication will be published on this blog.

Thanks.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

"Holiday Affair" - 1949

“Holiday Affair” (1949) could almost be an extension of the “war stories” series we did a couple weeks ago, with its examination of a war widow still fighting the good fight on the home front. The trouble is, the war’s over and she cannot make herself move on.

Janet Leigh plays the single mother of little Timmy, played with all-American boy golly gosh sweetness by young Gordon Gebert. Master Gebert has a cute line when, given a present he especially wanted, replies, “I’m so happy if I was a dog, my tail would be wagging.” It’s something a six-year would say.

A war widow, Janet Leigh still keeps the lamp in the window by subconsciously, and sometimes consciously, raising her boy to be a replacement for his father, and by not allowing a new husband and father a place in her heart.

Not that Wendell Corey isn’t trying. He plays her attorney beau, a steady, nice guy with an easy, intelligent manner who waits patiently for her to accept his marriage proposal, washes the dishes with her, and meanwhile works hard at being Timmy’s pal. Timmy is ambivalent, for his mother is raising him to be, like her, self sufficient and needing nobody but each other.

Enter Robert Mitchum, just as good at being a charming sweetie as he is being a sadistic scary guy. Who’d have thought? He and Miss Leigh cross paths in a department store, and continue to cross paths throughout the movie in situations both coincidental and contrived. He wins Timmy over first with his playfulness and man-to-man camaraderie, but Janet Leigh is more resilient. He has to hammer home some painful truths to her before she allows the war to be finally over.

I like the scene where Mitchum and Corey ruminate on how it doesn’t seem to snow as much as when they were kids, and how Corey muses it might have something to do with the atom bomb.

As we mentioned in our last post on “The Shop Around the Corner”, we’re looking at a commercial Christmas in these posts. What had been a cozy and quaint 1930s gift shop on a snowy Budapest side street in that movie becomes a bustling downtown post-war department store here. The kind of scene for which many old movie buffs are, in these days of mega malls and online shopping, nostalgic for, despite how the inconvenient dressing up and taking a cab downtown would seem today.

We love this old stuff, but I wonder if we have the guts and stamina, and patience for it?

Particularly clever is the use of electric trains, the iconic Holy Grail of Christmas presents, and also a foreshadowing of a cross-country train trip Mr. Mitchum intends to take to start his life over.

When the opening credits roll, we are shown a train barreling by, and as the camera pans back from the countryside, we see that it is nothing more than a toy electric train setup in a store toy department. Robert Mitchum takes center stage, part Pied Piper and part pitchman, as he demonstrates the marvelous toy trains to the rapt audience of kids. He is a salesman here, a hero to his young customers, a bane to the suspicious floorwalker who keeps an eye on him.

Janet Leigh buys a train, but not for her little boy who would kill for one. She is a comparison shopper incognito, a kind of commercial spy who investigates prices, quality of merchandise, buys trains and then returns them. Mr. Mitchum is on to her, but when he fails to report her to the manager, his floorwalker nemesis turns him in, and he’s fired. Out of job at Christmas.

His dream is to travel to California and work at a boat building business, but he needs the dough to get there. Still, he buys Timmy the train he won’t otherwise get for Christmas, and puts himself next in line behind Wendell Corey for Janet Leigh’s hand in marriage. If she can just realize the fact that she’s free to marry.

A couple of good scenes are the Christmas dinner with Janet Leigh’s in-laws, a kindly elderly couple, played by Esther Dale and Griff Barnett, doting on the grandson who reminds them so much of their deceased son. Wendell Corey and Robert Mitchum also have seats at the table, and for a while it’s very pleasant how these grownups behave so grown up, suppressing their own angst and desires for the sake of Christmas.

They give toasts, and when it’s Mr. Mitchum’s turn, he frankly states his case, in lawyer-like fashion, to the lady and her lawyer that he wants to marry her. Rarely has a personal confrontation come off as so classy.

It’s also a punch in the gut for Wendell Corey to have to sit through it, for Janet Leigh who fears it, and for her in-laws, who gamely suffer the logical discussion of who is better to be their grandson’s next father, a replacement for their son.

Another good scene is when Mitchum calmly blasts her between the eyes with self knowledge at its most uncomfortable, of what she is doing to herself and her son by not letting go of her widowhood.

Likewise when Wendell Corey breaks off with her, acknowledging to her what he has known for some time, she just doesn’t love him. It’s killing him, but he faces it stoically. Neither men try to beat each other’s time; they just want the facts which Janet Leigh is too frightened, or guilty to face.

Just before the end credits roll, we see a real train trip and watch Robert Mitchum take off on his new life adventure, but not alone. Just as at the beginning, the camera pulls back and the train cleverly becomes a toy again on a new train setup with tiny palm trees of his California destination. It’s like “Holiday Affair Meets Gumby.”

By the way, this film was released on Christmas Eve, 1949. In this previous post, we covered how most Christmas-themed movies were not released during the holiday at all.

Thanks for shopping with me this week. And for carrying the packages. You can put them down, now. For those who celebrate Christmas, I wish you a peaceful and pleasant holiday.

For all readers of this blog, I have a gift (should you choose to accept it, as they used to say on “Mission Impossible”). For today only you can order my novel “Meet Me in Nuthatch” FREE from Smashwords. This is an ebook, which can be downloaded to any ebook reader in different formats, and can also be downloaded to your computer and read on your computer without needing any Kindle or Nook or other ereader. When you go through the checkout, put in this coupon code: JQ29S -- and your book will be free.

Merry Christmas.

Janet Leigh plays the single mother of little Timmy, played with all-American boy golly gosh sweetness by young Gordon Gebert. Master Gebert has a cute line when, given a present he especially wanted, replies, “I’m so happy if I was a dog, my tail would be wagging.” It’s something a six-year would say.

A war widow, Janet Leigh still keeps the lamp in the window by subconsciously, and sometimes consciously, raising her boy to be a replacement for his father, and by not allowing a new husband and father a place in her heart.

Not that Wendell Corey isn’t trying. He plays her attorney beau, a steady, nice guy with an easy, intelligent manner who waits patiently for her to accept his marriage proposal, washes the dishes with her, and meanwhile works hard at being Timmy’s pal. Timmy is ambivalent, for his mother is raising him to be, like her, self sufficient and needing nobody but each other.

Enter Robert Mitchum, just as good at being a charming sweetie as he is being a sadistic scary guy. Who’d have thought? He and Miss Leigh cross paths in a department store, and continue to cross paths throughout the movie in situations both coincidental and contrived. He wins Timmy over first with his playfulness and man-to-man camaraderie, but Janet Leigh is more resilient. He has to hammer home some painful truths to her before she allows the war to be finally over.

I like the scene where Mitchum and Corey ruminate on how it doesn’t seem to snow as much as when they were kids, and how Corey muses it might have something to do with the atom bomb.

As we mentioned in our last post on “The Shop Around the Corner”, we’re looking at a commercial Christmas in these posts. What had been a cozy and quaint 1930s gift shop on a snowy Budapest side street in that movie becomes a bustling downtown post-war department store here. The kind of scene for which many old movie buffs are, in these days of mega malls and online shopping, nostalgic for, despite how the inconvenient dressing up and taking a cab downtown would seem today.

We love this old stuff, but I wonder if we have the guts and stamina, and patience for it?

Particularly clever is the use of electric trains, the iconic Holy Grail of Christmas presents, and also a foreshadowing of a cross-country train trip Mr. Mitchum intends to take to start his life over.

When the opening credits roll, we are shown a train barreling by, and as the camera pans back from the countryside, we see that it is nothing more than a toy electric train setup in a store toy department. Robert Mitchum takes center stage, part Pied Piper and part pitchman, as he demonstrates the marvelous toy trains to the rapt audience of kids. He is a salesman here, a hero to his young customers, a bane to the suspicious floorwalker who keeps an eye on him.

Janet Leigh buys a train, but not for her little boy who would kill for one. She is a comparison shopper incognito, a kind of commercial spy who investigates prices, quality of merchandise, buys trains and then returns them. Mr. Mitchum is on to her, but when he fails to report her to the manager, his floorwalker nemesis turns him in, and he’s fired. Out of job at Christmas.

His dream is to travel to California and work at a boat building business, but he needs the dough to get there. Still, he buys Timmy the train he won’t otherwise get for Christmas, and puts himself next in line behind Wendell Corey for Janet Leigh’s hand in marriage. If she can just realize the fact that she’s free to marry.

A couple of good scenes are the Christmas dinner with Janet Leigh’s in-laws, a kindly elderly couple, played by Esther Dale and Griff Barnett, doting on the grandson who reminds them so much of their deceased son. Wendell Corey and Robert Mitchum also have seats at the table, and for a while it’s very pleasant how these grownups behave so grown up, suppressing their own angst and desires for the sake of Christmas.

They give toasts, and when it’s Mr. Mitchum’s turn, he frankly states his case, in lawyer-like fashion, to the lady and her lawyer that he wants to marry her. Rarely has a personal confrontation come off as so classy.

It’s also a punch in the gut for Wendell Corey to have to sit through it, for Janet Leigh who fears it, and for her in-laws, who gamely suffer the logical discussion of who is better to be their grandson’s next father, a replacement for their son.

Another good scene is when Mitchum calmly blasts her between the eyes with self knowledge at its most uncomfortable, of what she is doing to herself and her son by not letting go of her widowhood.

Likewise when Wendell Corey breaks off with her, acknowledging to her what he has known for some time, she just doesn’t love him. It’s killing him, but he faces it stoically. Neither men try to beat each other’s time; they just want the facts which Janet Leigh is too frightened, or guilty to face.

Just before the end credits roll, we see a real train trip and watch Robert Mitchum take off on his new life adventure, but not alone. Just as at the beginning, the camera pulls back and the train cleverly becomes a toy again on a new train setup with tiny palm trees of his California destination. It’s like “Holiday Affair Meets Gumby.”

By the way, this film was released on Christmas Eve, 1949. In this previous post, we covered how most Christmas-themed movies were not released during the holiday at all.

Thanks for shopping with me this week. And for carrying the packages. You can put them down, now. For those who celebrate Christmas, I wish you a peaceful and pleasant holiday.

For all readers of this blog, I have a gift (should you choose to accept it, as they used to say on “Mission Impossible”). For today only you can order my novel “Meet Me in Nuthatch” FREE from Smashwords. This is an ebook, which can be downloaded to any ebook reader in different formats, and can also be downloaded to your computer and read on your computer without needing any Kindle or Nook or other ereader. When you go through the checkout, put in this coupon code: JQ29S -- and your book will be free.

Merry Christmas.

Monday, December 20, 2010

The Shop Around the Corner - 1940

The Shop Around the Corner (1940) nostalgically shows us the finely delineated everyday moments that are more trying, require more patience and courage, give more delight and a bigger emotional rush than even the most hectic modern countdown to Christmas. Reportedly director Ernst Lubitsch’s favorite film, it is no one wonder, for there is so much of his personally constructed Gemütlichkeit. It begins with the lilting, breezy dance orchestra music we hear at the opening and closing credits.

We’re going shopping this week with a look at the commercial aspect (though incidental) of Christmas as seen through this film, and on Thursday, with Holiday Affair (1949) here.

There are so many charming aspects to The Shop Around the Corner, most especially that the minor character actors play major roles, including many beautiful solo moments that complement the major stars here: Margaret Sullavan and James Stewart.

You’ll remember Felix Bressart from a slew of films, even if you don’t know his name. Here he is the elder shop clerk who assiduously avoids the blustering boss with whom he knows he can’t win, and seems to bring the warmth of his simple home where he is “Papa” to his wife and children, into the gift shop where he and his fellow employees have a kind of second home. We last saw him in this post on Portrait of Jennie (1949) where he played the befuddled movie projector operator.

You’ll remember Sara Haden as Aunt Milly from a long parade of Andy Hardy movies. She is the old maid secretary here instead of the old maid aunt. Charles Halton is the detective, also seen in dozens of movies in minor roles, probably you’ll recall him as the bank examiner in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

William Tracy is a standout as the clownish, clever delivery boy, likable and conniving, who eventually gets a promotion and lords it over the new delivery boy.

The new boy is played by a young Charles Smith, who could tear our hearts out with his gentle innocence and hopefulness.

Josef Schildkraut, who won the Best Supporting Oscar for The Life of Emile Zola (1937), continues to prove his versatility as the two-faced sales clerk always trying to stab his fellow employees in the back (we’ve all known them).

There is Frank Morgan, just off The Wizard of Oz (1939), who skillfully trades his customary comic confusion for a more dramatic role as the fussy boss, Mr. Matuschek, whose personal anxieties and ultimate near-tragedy affect his entire staff.

All these players make the movie seem like an ensemble piece, where the last shall be first. Still, there is a major plot line for the two stars apart from the goings on in the store.

Especially good in his role is James Stewart, the head sales clerk, a man who must be a buffer between the mercurial whims of the boss, and the helpless junior staff. Mr. Stewart has the ability to play that kind of young man who, while being street-wise and knowing the odds of life are stacked against him, manages to balance his wry pragmatism with a brave idealism that buoys him. He walks a fine line in his relationship with his boss, and with his secret love, a woman he knows only by her letters. We saw recently with Love Letters how much can be won, and lost, in precious correspondence and the allure of a well-turned phrase.

Margaret Sullavan plays the newest member of the staff, who cleverly and with chutzpah manages to charm a disinterested lady customer into buying unmovable merchandise, thereby getting herself a job and starting her role as a thorn in the side of James Stewart. They are combative throughout the film, but each has a secret. Eventually, we come to understand that the anonymous pen pal letters they write to prospective sweethearts are actually written to each other.

The story has been remade in several incarnations, including the post here on In the Good Old Summertime (1944). But this version has a charm all its own, and I think a good part of it is Lubitsch’s setting the story in Budapest during the Depression. I love the signs all written in Magyar, including our many peeks at the currency tabs on the cash register.

Miss Sullavan, with her Dresden doll features and her precise stage speech with her throaty voice seems to carry the illusion of Europe, as does, ironically, James Stewart. We may see him usually as his “Mr. Smith” icon, the all-American idealist. But there was also something, as mentioned above, of a practical, doubting, soberness to James Stewart’s portrayals, as if he is someone who was fooled once and is determined not to be taken in again. His gentlemanly reserve fits well here in this middle European gift shop.

I love Felix Bressart’s low bows when shaking hands. The Americans and the Europeans in the cast seem to blend well together, without parody.

Made in 1940, while World War II stripped away the independence and the lives of many, many Europeans, we may well guess that this is Mr. Lubitsch’s tribute, and perhaps farewell, to a more peaceful era in Europe. Hitler may have been well forming his plans in the 1930s, but there is still in this movie something decidedly nostalgic, something Habsburgian about this setting. It might be the cigarette boxes that play “Ochi Tchornya” (Dark Eyes), or the courtly shrug of the shoulders attitude that one must make the best of things in this troubled world.

The commercial aspect of Christmas here is gently expressed. Certainly, Frank Morgan exhorts, and bullies, his employees into gearing up for the hoped-for Christmas rush. Christmas Eve, a light snow without sleet or the slightest breeze falls on the shoulders of the shoulder-to-shoulder crowd in the street, teased by decorated window displays. Mr. Morgan’s gift shop does the best business since 1928, the last Christmas before the Wall Street crash.

I like James Stewart’s line to Felix Bressart when they discuss the excitement of getting a bonus, the anticipation of opening the pay envelope and wondering how much. “As long as the envelope’s closed, you’re a millionaire.”

We sense the boss is made the happiest when, after inquiring after the Christmas Eve plans of his employees, who all have somewhere to go, his newest staff member, young Rudy, is all alone this night. Boss, alone himself, joyfully invites delivery boy to a first-rate restaurant feast as Mr. Morgan learns the true spirit of Christmas, not from ghosts, but by his own errors, his near-tragedy, and his gratitude that life does go on in spite of how much of a mess we make of it sometimes.

If you’ve not seen The Shop Around the Corner, TCM is showing it tonight.

Come back Thursday for Robert Mitchum and Janet Leigh in a much larger department store setting in Holiday Affair here.

We’re going shopping this week with a look at the commercial aspect (though incidental) of Christmas as seen through this film, and on Thursday, with Holiday Affair (1949) here.

There are so many charming aspects to The Shop Around the Corner, most especially that the minor character actors play major roles, including many beautiful solo moments that complement the major stars here: Margaret Sullavan and James Stewart.

You’ll remember Felix Bressart from a slew of films, even if you don’t know his name. Here he is the elder shop clerk who assiduously avoids the blustering boss with whom he knows he can’t win, and seems to bring the warmth of his simple home where he is “Papa” to his wife and children, into the gift shop where he and his fellow employees have a kind of second home. We last saw him in this post on Portrait of Jennie (1949) where he played the befuddled movie projector operator.

You’ll remember Sara Haden as Aunt Milly from a long parade of Andy Hardy movies. She is the old maid secretary here instead of the old maid aunt. Charles Halton is the detective, also seen in dozens of movies in minor roles, probably you’ll recall him as the bank examiner in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

William Tracy is a standout as the clownish, clever delivery boy, likable and conniving, who eventually gets a promotion and lords it over the new delivery boy.

The new boy is played by a young Charles Smith, who could tear our hearts out with his gentle innocence and hopefulness.

Josef Schildkraut, who won the Best Supporting Oscar for The Life of Emile Zola (1937), continues to prove his versatility as the two-faced sales clerk always trying to stab his fellow employees in the back (we’ve all known them).

There is Frank Morgan, just off The Wizard of Oz (1939), who skillfully trades his customary comic confusion for a more dramatic role as the fussy boss, Mr. Matuschek, whose personal anxieties and ultimate near-tragedy affect his entire staff.

All these players make the movie seem like an ensemble piece, where the last shall be first. Still, there is a major plot line for the two stars apart from the goings on in the store.

Especially good in his role is James Stewart, the head sales clerk, a man who must be a buffer between the mercurial whims of the boss, and the helpless junior staff. Mr. Stewart has the ability to play that kind of young man who, while being street-wise and knowing the odds of life are stacked against him, manages to balance his wry pragmatism with a brave idealism that buoys him. He walks a fine line in his relationship with his boss, and with his secret love, a woman he knows only by her letters. We saw recently with Love Letters how much can be won, and lost, in precious correspondence and the allure of a well-turned phrase.

Margaret Sullavan plays the newest member of the staff, who cleverly and with chutzpah manages to charm a disinterested lady customer into buying unmovable merchandise, thereby getting herself a job and starting her role as a thorn in the side of James Stewart. They are combative throughout the film, but each has a secret. Eventually, we come to understand that the anonymous pen pal letters they write to prospective sweethearts are actually written to each other.

The story has been remade in several incarnations, including the post here on In the Good Old Summertime (1944). But this version has a charm all its own, and I think a good part of it is Lubitsch’s setting the story in Budapest during the Depression. I love the signs all written in Magyar, including our many peeks at the currency tabs on the cash register.

Miss Sullavan, with her Dresden doll features and her precise stage speech with her throaty voice seems to carry the illusion of Europe, as does, ironically, James Stewart. We may see him usually as his “Mr. Smith” icon, the all-American idealist. But there was also something, as mentioned above, of a practical, doubting, soberness to James Stewart’s portrayals, as if he is someone who was fooled once and is determined not to be taken in again. His gentlemanly reserve fits well here in this middle European gift shop.

I love Felix Bressart’s low bows when shaking hands. The Americans and the Europeans in the cast seem to blend well together, without parody.

Made in 1940, while World War II stripped away the independence and the lives of many, many Europeans, we may well guess that this is Mr. Lubitsch’s tribute, and perhaps farewell, to a more peaceful era in Europe. Hitler may have been well forming his plans in the 1930s, but there is still in this movie something decidedly nostalgic, something Habsburgian about this setting. It might be the cigarette boxes that play “Ochi Tchornya” (Dark Eyes), or the courtly shrug of the shoulders attitude that one must make the best of things in this troubled world.

The commercial aspect of Christmas here is gently expressed. Certainly, Frank Morgan exhorts, and bullies, his employees into gearing up for the hoped-for Christmas rush. Christmas Eve, a light snow without sleet or the slightest breeze falls on the shoulders of the shoulder-to-shoulder crowd in the street, teased by decorated window displays. Mr. Morgan’s gift shop does the best business since 1928, the last Christmas before the Wall Street crash.

I like James Stewart’s line to Felix Bressart when they discuss the excitement of getting a bonus, the anticipation of opening the pay envelope and wondering how much. “As long as the envelope’s closed, you’re a millionaire.”

We sense the boss is made the happiest when, after inquiring after the Christmas Eve plans of his employees, who all have somewhere to go, his newest staff member, young Rudy, is all alone this night. Boss, alone himself, joyfully invites delivery boy to a first-rate restaurant feast as Mr. Morgan learns the true spirit of Christmas, not from ghosts, but by his own errors, his near-tragedy, and his gratitude that life does go on in spite of how much of a mess we make of it sometimes.

If you’ve not seen The Shop Around the Corner, TCM is showing it tonight.

Come back Thursday for Robert Mitchum and Janet Leigh in a much larger department store setting in Holiday Affair here.

*********

Jacqueline T. Lynch

is the author of Ann Blyth: Actress.

Singer. Star. and Memories

in Our Time - Hollywood Mirrors and Mimics the Twentieth Century. Her newspaper

column on classic films, Silver Screen, Golden Memories is syndicated

nationally.

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Now Playing - "I'll Be Seeing You"

Here's an ad for "I'll Be Seeing You" (1944), which we covered in this previous post. We've got the soldier, the beautiful girl, and a hint of scandal (prison) and romantic intrigue one wartime Christmas. But, we smack a great big photo of teenaged Shirley Temple in case the names of Selznick, Cotten, and Rogers aren't enough. Always hedge your bets.

Monday, December 13, 2010

Off Topic

Book review blog, “MotherLode” has recently reviewed my novel “Meet Me in Nuthatch”, available as an ebook through Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, and Smashwords.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

War Stories - Part 3 - "Love Letters" - 1945

“Love Letters” (1945) is our third and last in the series of “war stories”. It’s a love story, and a mystery that doesn’t really need The War as a backdrop, but this was a time when so many letters were written, and relationships begun on the strength of a chance meeting.

In many families, the wife said goodbye to the husband (or sweetheart) at the train station. She said welcome home to him (if she was lucky), three or four years later. The only way to communicate in the years between were by letters. They might meet again -- to resume their lives and their relationship -- as near strangers, unless the letters were particularly heartfelt, and the communication between them was open and honest.

I doubt in our age of instant, but often weak and meaningless, communication does the power of language ever come close to matching the importance it had during World War II.

Note: Ayn Rand co-wrote the script with the writer of the novel on this story is based, Christopher Massie.

Joseph Cotten, again here in his trademark role of the troubled, romantic loner, is an officer with the British Army in Italy. He pens the letters that his fellow officer, Roger Moreland, sends to his girlfriend. Roger, played by Robert Sully, is a boorish, self-centered cad, who, though unfaithful to this woman, is amused by the idea of winning her through Mr. Cotten’s tender prose.

Cotten is sick of the idea, and disgusted with himself for doing the chore, partly because he knows Roger is an ass, and partly because he fears he is falling in love with the woman who writes sensitive replies to his letters. He has a fiancée of his own, and he is growing apart from her. He seldom writes her, saving his deepest thoughts for Roger’s friend, Victoria.

“I was able to write to her all the things I was never able to say to any woman I know.” He says, and felt the ruse was innocent as long as the girl didn’t care. “But Victoria cared, understood.” He realizes Victoria has fallen in love, not with Roger as she believes, but with his letters.

“She’s in love with a man who doesn’t exist.”

Mr. Cotten demands the charade stop. He won’t write anymore, wants to know nothing more about her. When Cotten is seriously wounded and placed in a military hospital in Italy, he gets a letter from Roger, who has returned to England for training. Roger has married Victoria.

When Cotten is sent back to England to convalesce he learns from another pal that Roger is dead, not in the war but from an accident at home. This news nags at Mr. Cotten, because it means this Victoria is now a widow, and free, and a temptation in spite of himself. He also feels guilt for making possible what he suspects must have been a bad marriage. In a way, though it is never couched in these terms, it's as if he prostituted this earnest, romantic woman to a callous stranger.

He still wants no part of the charade he committed, and wants to distance himself from what he has done. But when his brother takes him to a party at a friend’s flat, Cotten meets Victoria even though he is not aware of it, mainly because she is not aware she is Victoria.

Victoria is played by Jennifer Jones in their second pairing after last year’s “Since You Went Away.” She goes by another name, because she has lost her memory. There is more intrigue to come, and we get bits and pieces a little at a time. I won’t give a play-by-play on the plot, that would ruin it, but we do learn that Roger was murdered, and Mr. Cotten discovers his letters played a part in a tragedy and the great mystery of Miss Jones’ amnesia.

Jennifer Jones is by turns ethereal, and also teasing and free spirited. This is also something of a trademark role for her, the fey innocent, but she appears more at ease in this film and less fragile than in some of her other work.

Ann Richards plays her friend, a woman who took Jones into her flat and cared for her when she was unable to take care of herself. Ann Richards also had minor roles in “Random Harvest” (see this post) and in “Sorry Wrong Number” (see this post here and here), but her film career ended in the early 1950s.

It’s difficult to believe she could not have been given better promotion by a studio in Hollywood and enjoyed a longer film career, as she has an engaging presence in this film. Her role is minor, but she shows a range of emotion and great chemistry with Joseph Cotten. Until Cotten falls in love with Jennifer Jones, one might suspect, and even wish, that she would get together with Cotten.

Notice the scene where, when Ann Richards wants to discuss the tragedy/mystery privately with Cotten, she sends Jennifer Jones to the store to get some porridge. She hands her their ration book. Since the UK imported most of their cereals (and a lot of other products), rationing was more severe there and lasted well beyond the war. Though the US had its own rationing program, I don’t think we rationed oatmeal (porridge). Maybe somebody can set me straight on that. Being the so-called “bread basket of the world” had its compensations.

We don’t see too many ration books of the day in the movies, and I’m not sure why. Possibly the government requested the cooperation of the film industry not to make too big a joke of them so that people would follow the rules and take their use seriously. Possibly they did not want to harp on (though an English setting in this movie, this was still an American-made movie for an American audience), shortages to an audience weary of them and doing its utmost to sacrifice.

Mr. Cotten takes up residence in a country cottage left to him by his deceased aunt, where he is looked after by rustic family retainer Cecil Kellaway (whom we saw in “Portrait of Jennie”, see here). Ian Wolfe plays a vicar, and Harry Allen a local farmer, both character actors who you might remember from “Mrs. Miniver”, which we reviewed in the second post on this series.

Gladys Cooper, who also teamed up with Jennifer Jones in “Song of Bernadette” (1943), see this previous post, plays Miss Jones’ guardian. She plays prominently in the tragedy/mystery, and she’s a shadowy figure for most of the film. It’s not until the very end we get her story and the truth about Victoria. It’s a good scene between Jones and Cooper, where they both reach back into their memories and describe a particular pivotal event, each finishing the other’s sentences.

The war in this movie, unlike in “Mrs. Miniver” and “The More the Merrier” is less on the surface of everyday life for these country dwellers and more in the fog-shrouded background, though there is one scene where Cotten, driving with Jones on winding lanes, does mention the gas rationing, “Since you love motoring so much, we’ll travel to the end of our coupons.”

Also, there is a scene with a wedding in what appear to be the bombed-out ruins of a church, evocative of the end of “Mrs. Miniver.” The war is still present in this movie, but it seems to be sliding into the background.

And I think that portrait of the little boy which figures in a couple of scenes that Joseph Cotten says is him as a child really was him. There is a similar photo in his autobiography, “Vanity Will Get You Somewhere” (Mercury House, Inc., San Francisco, 1987). In that book, he states that the photo was also used in “Shadow of a Doubt”.

The war is mostly represented in the letters he has written to her, and in his depression on coming home. He tells her, “Ever since I came back from the war, I’ve wanted to be alone. I’ve been miserable with other people. You’re the first one with whom I feel at peace.”

She replies, “That’s because you’re broken up inside almost the same as I am. You’ve been through the war and you can’t bear to look back.”

In this movie, and as World War II drifted into the past (the film was released in August 1945, after the Japanese surrender but before the formal surrender ceremonies in September), the generation that fought the war seemed to decide in large measure not to talk about it anymore. Many servicemen, like Joseph Cotten in the film, preferred not to look back.

Much of that war is documented in letters, and the intriguing notion that two people can fall in love without ever meeting each other…I would not hazard a guess as to how many times that actually happened. I don’t doubt that it did.

This is the end of our series on “war stories”. The all-clear has been sounded. Now get out of my cellar. I'd better not be missing any cans of SPAM.

In many families, the wife said goodbye to the husband (or sweetheart) at the train station. She said welcome home to him (if she was lucky), three or four years later. The only way to communicate in the years between were by letters. They might meet again -- to resume their lives and their relationship -- as near strangers, unless the letters were particularly heartfelt, and the communication between them was open and honest.

I doubt in our age of instant, but often weak and meaningless, communication does the power of language ever come close to matching the importance it had during World War II.

Note: Ayn Rand co-wrote the script with the writer of the novel on this story is based, Christopher Massie.

Joseph Cotten, again here in his trademark role of the troubled, romantic loner, is an officer with the British Army in Italy. He pens the letters that his fellow officer, Roger Moreland, sends to his girlfriend. Roger, played by Robert Sully, is a boorish, self-centered cad, who, though unfaithful to this woman, is amused by the idea of winning her through Mr. Cotten’s tender prose.

Cotten is sick of the idea, and disgusted with himself for doing the chore, partly because he knows Roger is an ass, and partly because he fears he is falling in love with the woman who writes sensitive replies to his letters. He has a fiancée of his own, and he is growing apart from her. He seldom writes her, saving his deepest thoughts for Roger’s friend, Victoria.

“I was able to write to her all the things I was never able to say to any woman I know.” He says, and felt the ruse was innocent as long as the girl didn’t care. “But Victoria cared, understood.” He realizes Victoria has fallen in love, not with Roger as she believes, but with his letters.

“She’s in love with a man who doesn’t exist.”

Mr. Cotten demands the charade stop. He won’t write anymore, wants to know nothing more about her. When Cotten is seriously wounded and placed in a military hospital in Italy, he gets a letter from Roger, who has returned to England for training. Roger has married Victoria.

When Cotten is sent back to England to convalesce he learns from another pal that Roger is dead, not in the war but from an accident at home. This news nags at Mr. Cotten, because it means this Victoria is now a widow, and free, and a temptation in spite of himself. He also feels guilt for making possible what he suspects must have been a bad marriage. In a way, though it is never couched in these terms, it's as if he prostituted this earnest, romantic woman to a callous stranger.

He still wants no part of the charade he committed, and wants to distance himself from what he has done. But when his brother takes him to a party at a friend’s flat, Cotten meets Victoria even though he is not aware of it, mainly because she is not aware she is Victoria.

Victoria is played by Jennifer Jones in their second pairing after last year’s “Since You Went Away.” She goes by another name, because she has lost her memory. There is more intrigue to come, and we get bits and pieces a little at a time. I won’t give a play-by-play on the plot, that would ruin it, but we do learn that Roger was murdered, and Mr. Cotten discovers his letters played a part in a tragedy and the great mystery of Miss Jones’ amnesia.

Jennifer Jones is by turns ethereal, and also teasing and free spirited. This is also something of a trademark role for her, the fey innocent, but she appears more at ease in this film and less fragile than in some of her other work.

Ann Richards plays her friend, a woman who took Jones into her flat and cared for her when she was unable to take care of herself. Ann Richards also had minor roles in “Random Harvest” (see this post) and in “Sorry Wrong Number” (see this post here and here), but her film career ended in the early 1950s.

It’s difficult to believe she could not have been given better promotion by a studio in Hollywood and enjoyed a longer film career, as she has an engaging presence in this film. Her role is minor, but she shows a range of emotion and great chemistry with Joseph Cotten. Until Cotten falls in love with Jennifer Jones, one might suspect, and even wish, that she would get together with Cotten.

Notice the scene where, when Ann Richards wants to discuss the tragedy/mystery privately with Cotten, she sends Jennifer Jones to the store to get some porridge. She hands her their ration book. Since the UK imported most of their cereals (and a lot of other products), rationing was more severe there and lasted well beyond the war. Though the US had its own rationing program, I don’t think we rationed oatmeal (porridge). Maybe somebody can set me straight on that. Being the so-called “bread basket of the world” had its compensations.

We don’t see too many ration books of the day in the movies, and I’m not sure why. Possibly the government requested the cooperation of the film industry not to make too big a joke of them so that people would follow the rules and take their use seriously. Possibly they did not want to harp on (though an English setting in this movie, this was still an American-made movie for an American audience), shortages to an audience weary of them and doing its utmost to sacrifice.

Mr. Cotten takes up residence in a country cottage left to him by his deceased aunt, where he is looked after by rustic family retainer Cecil Kellaway (whom we saw in “Portrait of Jennie”, see here). Ian Wolfe plays a vicar, and Harry Allen a local farmer, both character actors who you might remember from “Mrs. Miniver”, which we reviewed in the second post on this series.

Gladys Cooper, who also teamed up with Jennifer Jones in “Song of Bernadette” (1943), see this previous post, plays Miss Jones’ guardian. She plays prominently in the tragedy/mystery, and she’s a shadowy figure for most of the film. It’s not until the very end we get her story and the truth about Victoria. It’s a good scene between Jones and Cooper, where they both reach back into their memories and describe a particular pivotal event, each finishing the other’s sentences.

The war in this movie, unlike in “Mrs. Miniver” and “The More the Merrier” is less on the surface of everyday life for these country dwellers and more in the fog-shrouded background, though there is one scene where Cotten, driving with Jones on winding lanes, does mention the gas rationing, “Since you love motoring so much, we’ll travel to the end of our coupons.”

Also, there is a scene with a wedding in what appear to be the bombed-out ruins of a church, evocative of the end of “Mrs. Miniver.” The war is still present in this movie, but it seems to be sliding into the background.

And I think that portrait of the little boy which figures in a couple of scenes that Joseph Cotten says is him as a child really was him. There is a similar photo in his autobiography, “Vanity Will Get You Somewhere” (Mercury House, Inc., San Francisco, 1987). In that book, he states that the photo was also used in “Shadow of a Doubt”.

The war is mostly represented in the letters he has written to her, and in his depression on coming home. He tells her, “Ever since I came back from the war, I’ve wanted to be alone. I’ve been miserable with other people. You’re the first one with whom I feel at peace.”

She replies, “That’s because you’re broken up inside almost the same as I am. You’ve been through the war and you can’t bear to look back.”

In this movie, and as World War II drifted into the past (the film was released in August 1945, after the Japanese surrender but before the formal surrender ceremonies in September), the generation that fought the war seemed to decide in large measure not to talk about it anymore. Many servicemen, like Joseph Cotten in the film, preferred not to look back.

Much of that war is documented in letters, and the intriguing notion that two people can fall in love without ever meeting each other…I would not hazard a guess as to how many times that actually happened. I don’t doubt that it did.

This is the end of our series on “war stories”. The all-clear has been sounded. Now get out of my cellar. I'd better not be missing any cans of SPAM.

Monday, December 6, 2010

War Stories Part 2 - "The More the Merrier"

Fair warning, I'm going to discuss pretty much the entire movie, so if you don't want to know the details, stick your fingers in your ears and sing, "La, la, la, la!" for the next half hour.

“The More the Merrier” (1943) brings the war story back to this side of pond now that the U.S. had entered the fighting and Americans had learned what it was to be, sort of, deprived. Americans had a different experience from Mrs. Miniver and family, and we handled The War with not so much with a stiff upper lip, as with a wisecrack. Tomorrow, December 7th, marks the anniversary of our reason for joining the fighting.

The main gag driving the film is the wartime housing shortage. For the first time in U.S. history, masses of people were moving all over the country at the same time. Servicemen and women were leaving home for military camps and then to points of embarkation. Young brides, those that could, followed inductee husbands to new posts stateside. Big cities called to a still mostly rural America to fill slots in war factories and civil government.

“The More the Merrier” is set in Washington, D.C., and teases us not only on the housing shortage, but on the befuddled bureaucracy of a democratic republic. The faux travelogue at the beginning reminds us we are in a city disparagingly once described as a place of Southern efficiency and Northern charm.

That used to be a joke. Son.

The second running theme is introduced when Charles Coburn, a consultant to the government on the housing shortage, admires the statue of Admiral David Farragut, whose famous directive during the American Civil War at the Battle of Mobile Bay you’ll recall was, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” It is Mr. Coburn’s motto, too. He gets his own affairs and the affairs of others which are none of his business briskly managed with this war cry.

It also reflects wartime cheerleading to a frightened audience.

He shouts this motto so often, that one wonders if his exuberance is really because he gets to say the word “damn” with impunity. Evidently this caused less fuss than when Clark Gable uttered the cuss word in “Gone with the Wind” (1939) a mere four years earlier. You could say the dam broke.

Several other themes weave their way through this film, like the shortage of men leading to more women leaving the home and entering the workforce. The shortage of men also makes them a valued commodity, and turns women from the pursued into the pursuers. There is a scene in the movie where a line of women wait to punch in a time clock, and they tease a lone young man with whistles and catcalls that unnerves him into running away.

Charles Coburn has arrived in the city too early for the hotel reservation made for him, so he tricks his way past a line of applicants to take the room for rent offered by Jean Arthur. She is also a government worker, and she has a small flat with an extra bedroom that she has chosen to rent to serve her country.

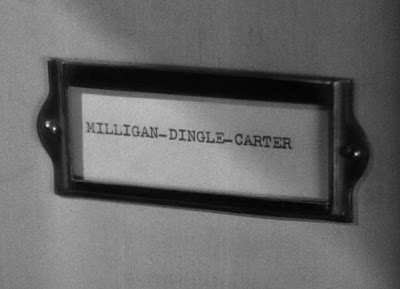

Jean Arthur was nominated for an Oscar for this role, and Charles Coburn won Best Supporting for his role as Mr. Dingle. They had first teamed up for “The Devil and Miss Jones” (1941), and their wonderfully silly rapport is repeated here. He becomes a nosy, pushy sort of fairy godfather, not merely because he just likes to run everything, but also because he senses immediately, as do we, that Miss Arthur is drowning in her own lack of spontaneity. As she wails later on in the film, “I’m not the kind of person anything happens to!”

It is not until Coburn barges his way into her life that she begins to realize how empty her life has been.

She is reticent to take him on as a roomer because she prefers to have a woman living with her. She finally agrees to let him stay, but adds a caveat that they must be careful not to be seen coming and going together. Coburn’s rakish, proud, smile is so cute as he begins to understand she is afraid the neighbors will think they are shacking up, just one of the many instances they play off each other so well. He thanks her for the compliment.

More than most other very fine, but more “stagy” actresses in this glamorous era, Jean Arthur played her roles with a natural and almost otherworldly believability. She is identified mainly as a comedienne, but I think she was really a dramatic actress in comic roles, and that gave her a multidimensional quality far beyond just broadly playing clowns. Someone else in this role might appear shallow, and buffoonish. Miss Arthur makes this brittle woman interesting, and lovably obtuse. Along with her famous sure-fire comedic timing she adds a touch of pathos.

Perhaps her ability to remain so deeply in character, so locked in the moment, was a defense mechanism that enabled Jean Arthur, extremely shy and insecure in real life, to do her job. Many of her roles, coincidentally or not so coincidentally, were women who found themselves undergoing a metamorphosis, responding to deeply buried passions when stimulated by challenges, crisis, and in this film at least, a strong case of sexual arousal brought on by Joel McCrea. That happens later.

First, a little slapstick. A long scene (which I would have loved to have seen in rehearsal), of Coburn’s and Arthur’s first morning together, each with a timed set of tasks to accomplish before they head off to their respective jobs. Coburn calls it the steeplechase. A running gag involving his pants that keep disappearing and reappearing is mapped out well, and looks like a silent movie scenario.

Another funny bit is when he locks himself out of the apartment while Jean is in the bathroom brushing her teeth. Here’s where we get another glimpse at Miss Arthur’s unadorned believability. Yes, the toothpaste froth around her mouth dripping like a rabid dog is funny; she is not afraid of looking foolish. However, look at her eyes.

Though she looks into the mirror, it is an empty gaze. She inspects her ear as she scrubs her teeth. She looks like her mind is wandering. This is exactly what we do when we brush our teeth. Our minds wander. We are thinking about work, about picking up the kids at school, about what to wear, but the last thing we think about while brushing our teeth is brushing our teeth. She was meticulous about being natural.

“War brings people closer together,” Mr. Coburn states, and in large measure it did. We will see in the film numerous examples of crowding and inconvenience that would probably send people today, who seem to have a greater sense of entitlement, into rants and possible acts of revenge. Back then the greatest ranting, revenge, and sense of entitlement was to be found in Hitler or Mussolini. Nobody wanted to be like those guys.

Another aspect of life then that does not translate to today is the running gag on awkward grammar. Coburn shows his comic finesse with little more than dropping prepositions after a moment of wondering what to do with the leftovers, such as “because she borrowed it to go to it. In.”

He does this a few times and it’s quite funny, but today in a world of, “Uh, I’m, like, you know, whatever…” people speaking stupidly is the norm. When stupid is normal, it’s not funny. Also, breaking social rules is not an effective gag anymore when we live in a society where pretty much any behavior is accepted or tolerated. Breaking the rules is not daring or funny when there are no rules. (This is not meant to be a societal judgment, only a comment about script conventions.)

Obviously, Jean Arthur’s puritan worries about being caught living with men is also no longer standard today, so that joke may stretch very thin here. But perhaps the biggest theme moving the plot is also one that takes some translation. The War. It’s the reason why they’re all together here, it’s reason why Jean is renting her spare room, it’s the reason why Coburn and Joel McCrea need it, it’s the reason why the plot thickens, complications arise, new worlds open up, dreams are dashed, and why they must go on in spite of everything.

But, where was The War, exactly? Mrs. Miniver had it in her back garden, in her destroyed dining room, in the body of her dead daughter-in-law sprawled on the floor. When the enemy arrived in our country, it was as prisoners, and they were tucked safely into POW camps. Most people never saw them.

Here the war is less an effort to survive (though it would be if things got any worse), but more a sense of guilt and unrelenting responsibility. It may be difficult for younger audiences to comprehend how a war fought somewhere else could be so pervasive, could dominate every facet of daily life here, and demand personal sacrifice unheard of today.

We know of the tremendous sacrifices of service personnel in that war. What few people recall today is that a good part of the civilian population worked themselves nearly to death during those years. They had little support, only constant reminding not to complain. Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.

But, this is a comedy, so we hint at these subjects with typical American wisecracks. This is what makes this film so quintessentially American. We may exhibit a bit of awkwardness trying to interpret Mrs. Miniver’s wartime Britain, but here were are on home turf.

Flippancy makes things seem normal even when the world is upside down. Flippancy covers immense national anxiety, perhaps as much as Jean Arthur's smooth comic timing masks hers.

Back to Jean and her roomie. We discover a hint of loneliness in this rigid woman’s austere personality when she writes in her diary about Coburn, “At least someone around the house to break the silence.” He senses her social backwardness, and decides to play matchmaker when Joel McCrea stands out on the sidewalk with his suitcase and a large propeller over his shoulder. Coburn rents his half of his room, which has two beds in it, to McCrea.

Joel McCrea, as we will learn in small bits, is a mechanic from an airplane factory out in California, sent here to deliver what is probably classified aeronautic equipment to a Washington government department. In a few days, he is to be sent to North Africa as a sergeant on special assignment. Coburn decides Mr. McCrea is an eligible bachelor, but being eligible during World War II also meant eligible for military service. McCrea knows his dance card is full for the next few years, and he has no intention of getting involved with anybody in the meantime.

Joel McCrea, as we will learn in small bits, is a mechanic from an airplane factory out in California, sent here to deliver what is probably classified aeronautic equipment to a Washington government department. In a few days, he is to be sent to North Africa as a sergeant on special assignment. Coburn decides Mr. McCrea is an eligible bachelor, but being eligible during World War II also meant eligible for military service. McCrea knows his dance card is full for the next few years, and he has no intention of getting involved with anybody in the meantime.It is another intrusion of The War into this movie. McCrea knows where he is going, but he is still lost, between engagements. His life is not his own.

There is another slapstick scene of Jean Arthur and Joel McCrea not realizing the other is there, lots of just missing each other as they move from room to room. There is a cute moment where she is in her bedroom dancing to a rumba version of “What is This Thing Called Love”, glancing backward at her bum to see if she is sexy. It is our first clue there might be more to this schedule-obsessed wallflower.

Meanwhile, Joel, standing in the hall in his bathrobe, clutches his toiletries kit and starts to rumba as well. They are apart, but it is as if they dance together, a mating dance. We are, incidentally, treated to a tantalizing shot of Joel’s bare legs. More to come later.

A note here about rumba music (Yes, yes, I know. Just shut up already and talk about the “damn” movie.) A craze for Latin music began in the late 1930s and exploded during the war years, partly in response to our Pan-American re-awakening that we needed some allies in our own hemisphere. Maybe sometime we can go into the conga craze in movies. (You with the pencil, put that on our list of things to do.)

("The Devil and Miss Jones")

Just about everything you see in old movies is there for a reason. Well, maybe not everything…does it seem to you that the cropped top Jean is wearing in the rumba scene exposing her bare midriff is the same one she wore in the beach scene in “The Devil and Miss Jones” (1941)?

("The More the Merrier")

Back to Jean and Joel. Eventually each discovers the other and Mr. Coburn has some ‘splaing to do. Another cute bit with proper speech versus colloquial slang where the phrase, “six bucks” is passed back and forth between them.

“Well, give him back his six bucks.”

“I don’t have the six bucks. He gave you the six bucks.”

And Coburn dangles more prepositions, “And I’ll have the money to pay him. With.”

It’s only funny if you understand it’s bad English.

Jean relents and lets Joel stay. The next morning, our trio crams together in a little kitchen nook. Jean tries to keep to her precise schedule of eating her egg and getting ready for work, but here two big, hearty men sit down, invade her personal space, share her toast and make breakfast small talk. She is awkward at social banter, and we see her discomfort. She gradually displays a tentative willingness to be brought out of her shell that is as courageous as it is sweetly pathetic.

By the way, I love the dresser scarves in her apartment, that she has them. It’s such a miniscule touch that she wants things just so. She has precise standards. And the photograph of Abraham Lincoln on her desk.

She reveals she is engaged to a Mr. Pendergast, whom she always calls Mr. Pendergast. They chide her about his age, 42, and that he has kept her waiting at the altar nearly two years. We sense, and they know without meeting him yet, that Mr. Pendergast is a drip, whose career comes before Jean. When Joel gets on Jean’s nerves and the only bad thing she can think to call him is “messy”, he teases her that Mr. Pendergast must comb his hair constantly. She thinks she is putting Joel in his place when she retorts, “Mr. Pendergast has no hair!” and walks out.

Her “so, there!” moment falls dismally short of its mark, but she is saved from appearing ridiculous to the audience by stopping halfway down the stairs, glancing back, and thoughtfully half smiling to herself. They are now her boys, and they have become a kind of family.

Another wartime era moment is left to us when Jean Arthur boasts that Mr. Pendergast has had dinner at the White House, and Mr. Coburn replies, “Worst food in Washington.” By all accounts, during the Roosevelt years, it was.

One more topical war reference: Mr. Coburn uses the phrase “Eastern War Time”. Daylight saving time was established temporarily during World War I to save energy, and was re-introduced in 1942 for the same reason. We remained on daylight saving time the entire war, no changing the clocks, and this was referred to as War Time. (Somebody shut her up! Sit on her!)

On Sunday, the rooftops of D.C. become the playground of the apartment dwellers who all come up to catch some sun in an era where most people did not own cars, and even if you did, three gallons of gas per week was all you might be allotted by rationing.

Here’s Jean Arthur and co-workers driving in a car with an “A” gasoline rationing sticker on it, which would have allowed them about three gallons a week. Have a look here at this previous post on wartime gas rationing in the movies.

That wasn’t going to get you to the beach or out in the country for the day, even if pleasure motor trips were not banned by law (which they were). Off in the distance, we see the Capitol Dome, which we get several glimpses of in this movie. I suppose it’s like Paris: in the movies, every bedroom window has a view of the Eiffel Tower. Here it’s the Capitol Dome.

On the rooftops the neighbors pose for snapshots, read, paint, picnic, kids play war games with toy guns. War was probably the most popular child’s game during The War. While Toby Miniver clutches his cat’s tail in the backyard air raid shelter on another sound stage, these kids machine gun Charles Coburn for fun, who plays along and shoots back at them.

The “family” gathers on the roof with the Sunday paper and the portable record player, cushions and blankets. The director reminds us again how sexy Joel McCrea is by leaving him in the foreground in shorts and a beach robe opened to reveal his chest. In this world of government women, like Amazon warriors heading for the time clock, lazy, laconic Joel McCrea, must be, for this sweet pinup moment, the male Betty Grable. Like the small point about the dresser scarves, I love that he walks around in stocking feet, wearing white gym socks.

Jean sprawls on blanket nearby, knitting, and the boys read the Sunday funnies aloud to each other. She glances over them with a look that is half amused and half disapproving, like an elder sister forced to mind her younger brothers for the day.

Then Coburn really does the bratty kid brother act by reading her diary, and when she discovers, her “That was a miserable thing to do,” bleeds venom from her voice, and heartbreak because she has been humiliated. She learns what she has always suspected: it is risky to let people into her life.

She boots them out but later allows McCrea to remain because he has only a day left before he will join the Army and be shipped to Africa with his propeller.

Now we move into the romantic stage, for if it was Coburn that brought them together, his presence also keeps them apart. The family dynamic changes when a family member leaves, and both Joel and Jean grow up and discover each other now that they are on the island alone.

There’s a comically suspenseful scene when she waits for a call from Mr. Pendergast on whether or not he will decide to take her out on a date that evening. At a crucial moment, a teenage boy from downstairs named Morton, played by Stanley Clements, whom you may remember as the gang leader from “Going My Way” (1944), bursts in for advice from Jean. Note his “Jughead” hat (Archie Comics, you remember), which was popular among teens of that era. They took a man’s felt fedora hat, turned in up and cut the brim like a zigzag.

Don’t knock it. Someday tattoos are going to be funny.

He wants to know if he should join the Boy Scouts, and is as serious as if he were pondering joining the Army. She calls him her “fella”. Truly, they’re either too young or too old.

That was a song, by the way.

Eh, skip it. (I could sing it, but I won’t. I can see your attention is wavering.)

It’s a cute scene, and both Joel and Jean want to kill Morton for procrastinating. But Mr. Pendergast, who at last arrives to take Jean out for the evening, is the real party pooper.

But, the night is young, and Jean and Joel, and Mr. Coburn, and Mr. Pendergast all run into each other at a nightclub. Another cute moment when they are all sitting at a table, and a rumba plays in the distance. Both Jean and Joel, still seated, start to move their shoulders and succumb to the seductive rhythm. Mr. Coburn tells them to go dance so he can discuss business with Mr. Pendergast.

He keeps Mr. Pendergast, terrifically played with delightful self importance by Richard Gaines (who does a 180-degree turn in character when he plays Patrick Henry in “The Howards of Virginia” - see previous post), busy for the rest of the evening.

Jean sees Joel being ogled by a flock of other women, and she gets jealous and territorial in a way she never was over Mr. Pendergast. I love Mr. Gaines’ officious-sounding, radio announcer-quality voice. Mr. Pendergast, by the way, has a spectacularly ugly toupee that nobody mentions. It’s just there for all to see. Like the Capitol Dome.

When Joel escorts her home, we are treated to one of the most erotic and silly seduction scenes Hollywood ever produced. They walk down the street, passing lovers clutching each other in dark corners. They glance at these couples with interest and envy, as Jean tries to pry information out of Joel about his past, particularly his former girlfriends. She is apparently jealous of them, too. He takes her hand, her arm, puts his hand on her bare shoulder repeatedly as they walk all the while she smoothly, but without apparent alarm, plucks his hands from her person. It is like a dance.

They sit on the front steps of their apartment building, and talk more about her marriage plans with Mr. Pendergast. She continues to sing Mr. Pendergast’s praises while Joel slowly runs his hands over every part of her body the Production Code will let him. I don’t know how carefully this was rehearsed but some of it had to be improvised.

He clearly desires her, is doing everything but undressing her, but maintains a polite stream of conversation. If he just said “uh-huh” to her dialogue, as if ignoring what she is saying to him, it wouldn’t be as funny. Their equal determination to carry on the discipline of conversation despite their growing obsession with each other is a sparkling moment as comic as it is romantic. It’s like when they were doing the rumba separately, both preoccupied with their passions, but that time indulging them in secret.

Jean shows herself the master of both comedy and endearing emotion in this scene as she tries to soldier on through the proper social niceties and talking about her cousin’s stamp collection, battling to suppress her arousal as Joel explores her, kisses her neck, her hand, her bare shoulder. Her voice breaks. In perhaps the first spontaneous thing she ever did in her life, Jean takes Joel’s face in her hands and plants a kiss on him that makes him dizzy. Not bad for a first try. We have a feeling she’s been saving that one for a long time. They part breathlessly, but with polite formality, gathering bits of dignity they have left all over the steps.

The silliness never once lessens the steaminess of the scene. The sensuality never overwhelms the silliness. It’s a perfect marriage. THIS SCENE is why they call it “romantic comedy”.

Joel McCrea had, like Jean Arthur, a natural style so well suited to comedy, a quiet, light manner open to sudden dramatic shifts and surprising intensity. They were a great match, and this was their third and last film together. Another good scene, intimate and silly, is when they examine together all the compartments of the new travel bag he gives her. It’s really charming, with their low, quiet voices overlapping each other’s sentences, and you have to admire what two pros can do with a simple prop.

George Stevens directed this film, and responsible for much of its magic, worked particularly well with Jean Arthur. He also made her memorable final film “Shane” a decade later.

Early in the film, we are shown that the wall between her room and the spare bedroom is quite thin and Mr. Coburn and Jean can talk through the wall. Now, with Jean and Joel gone to their separate beds, we have a split screen effect of them in bed “together” that predates the similar device used in “Pillow Talk” (1959) with Rock Hudson and Doris Day. It is more erotic here, because they are not miles away in different apartments. Also, because they have more at stake. The scene decompresses from sexual tension into sorrowful tenderness when, after they have confessed their love for each other, realize that there’s not just a wall between them, it’s The War.

Yes, The War was that pervasive. It entered the bedroom as easily as it slipped into the workplace, the school, the wallet, the conscience, the subconscious. There was no escape.

It's sweet that she wears what looks like a gardenia in her hair for the evening out, and does not remove it when she goes to bed. If I wore a gardenia in my hair to bed, I'd wake up with petals up my nose.

Not that I've tried it. But I might sometime if curiosity got the better of me.

It might even be worth the embarrassement of going to the ear, nose, and throat doctor the next day to get the gardenia petals out of my nose.

There’s a bit more slapstick to go when suspicious young Morton has turned Joel into the FBI as a spy, another crowded cab ride shows us that gas rationing affected cabbies, too, who were not allowed to drive unless chair cabs were completely full of passengers, and when Joel and Jean succumb to a marriage of convenience arranged by Mr. Coburn to keep her reputation spotless. Lots of great dialogue, but this post is already stretching beyond the state line.

The last scene (yes, I know I’m telling you everything here. Don’t shush me. You’ve shushed your last shush, as Jean would say), brings the culmination of all the wartime crowding, the separation of lovers, and Admiral Farragut’s “damn the torpedoes” attitude.

Jean, miserable and crying over her cheap fake marriage, changes into a sexy negligee to sleep alone again. Joel goes dejectedly to the spare room to pack because he’s due to report for duty in a few hours. He demands she not take in any more roomers because of the riffraff she might attract, and she complains that he is already crabbing like a husband. A poignant moment when he pulls off his sprig of lily of the valley from his suit lapel (to match her wedding bouquet) and mutters, “Well, I am a husband…at least until it’s annulled.”

She cries and they lamely try to pick a fight with each other, when both suddenly realize the wall between their rooms is gone. Mr. Coburn has had workmen tear it out. Astonished, their reserve crumbles like the drywall.

Anguish turns to comedy, and then to sex when Joel and Jean, adopt slow, sly smiles. Jean’s crying has ceased, but she manufactures a few fake wails as a kind of mating call to demand comforting. Joel, who we’ve known from the beginning is her perfect mate, happily responds to the call of duty like any good bridegroom.

Full speed ahead.

But only until The War intrudes again.

Come back Thursday for our final post on “war stories” when we jump back across the pond to England and see that wartime deception has led to tragedy for Joseph Cotten and Jennifer Jones in “Love Letters.”

Have a look below at the silly seduction scene. Let me know what you think. (Don’t forget to scroll to the bottom of the page to mute the music so you can hear the video.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)