Katie Did It

(1951) has become an elusive sort of “holy grail” quest for me during this

year-long series on the career of Ann Blyth.

I left this spot open towards the end of the year figuring I would have

either the movie to discuss, or else have a metaphor for reason the bulk of Ann

Blyth’s career is largely forgotten and that she is looked upon by those who do

recall her work fondly as an “underrated

actress.”

Katie Did It

(1951) has become an elusive sort of “holy grail” quest for me during this

year-long series on the career of Ann Blyth.

I left this spot open towards the end of the year figuring I would have

either the movie to discuss, or else have a metaphor for reason the bulk of Ann

Blyth’s career is largely forgotten and that she is looked upon by those who do

recall her work fondly as an “underrated

actress.”

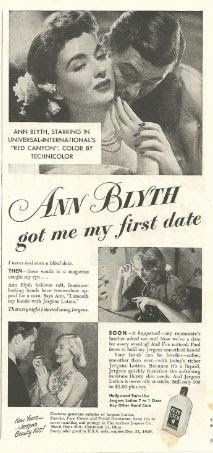

Ann plays Katherine Standish, a prudish small-town New

England librarian. Mark Stevens plays a

big-city commercial artist who comes to town, causing scandal when he paints

Ann in a provocative pose for an advertising campaign. Directed by Frederick de Cordova, this comedy

also features Craig Stevens and Cecil Kellaway.

There are no reviews on the IDMb website, only the sound of

crickets. Critic Leonard Maltin, as

posted on the TCM page for this movie, says:

“Ann Blyth is perkier than usual as square New England

librarian who becomes hep when romanced by swinging New Yorker Stevens.”

Not much to go on, but “perkier than usual” might seem to

indicate that Mr. Maltin has actually seen the film himself. I wonder.

Even the mighty TCM website (on which I confess, like the IDMb website,

I have found disappointing errors from time to time) is otherwise silent on this

unaccountably obscure film.

In the timeline of Ann’s movie career, Katie Did It is sandwiched between two big hits: the drama Our Very Own (1950) which we discussed here, and the musical, The Great Caruso (1951), which we discussed here. It

seems to have been obscured by them both.

We do have, however, a brief glimpse into the filming of

this movie from an article that discussed Ann’s “first day jitters” at the

start of a film.

“Everything is fine

until the minute I walk on the set for my first shot,” Miss Blyth said, “Then

my knees sort of buckle, sweat trickles out on my forehead and my tongue seems

to stick to the roof of my mouth…Yet I feel somehow that if I didn’t feel that

way, something would be wrong.”

“At the very

beginning, Freddie (director Frederick de Cordova) suddenly switched scenes on me,” she said, “Instead of doing the

sequence I came prepared for, he announced we’d shoot an entirely different

scene.”

It made her so busy

learning new lines and shuffling into another costume, that Ann didn’t have

time to remember to be jittery.

“Then he told me that

this was a deliberate attempt to put me at ease—after we’d made the scene. I was rather cross about it at first, until I

made the discovery that I’d breezed through the almost-unrehearsed sequence

with no trouble at all.”

The movie was never released on DVD or VHS, and to my

knowledge, has not been shown on TCM, but I hope someone will correct me. Failing this, I’m hoping that the film may

exist in a private collection or somebody’s warehouse or attic in 16mm form. If so, I’d be interested in buying it.

No film yet, but the metaphor? I would hesitate to hang Ann Blyth’s current reputation

among many to be an underrated or even unremembered actress just over one

“lost” film, not when there are so many other movies to give ample evidence of

her being a very gifted actress. But there is something else niggling in her

legacy to classic film buffs.

Here I quote from my discussion on my pal John Hayes’ blog Robert Frost’s Banjo a couple months

ago:

This woman had been the flavor of the month

all through the late 1940s and most of the 1950s, on enough magazine covers to

choke a horse, and as famous in her day as any young star could be. Today, she is nowhere to be seen in that

kitschy souvenir shop universe where classic film fans can easily snag T-shirts

and coffee cups and posters of Clark Gable and The Three Stooges, Mae West and

Betty Boop, and, of course, the ever-exploitable Marilyn Monroe.

Where was Ann Blyth? She never retired from performing. She had, unlike most other stars of that era,

performed in all media from radio to TV to stage, and was successful in all of

them. Far, far more talented than any

other 1950s glamour girl, yet she is not as well known today among younger

classic film fans. I wanted to know why.

Not that I am calling for Ann Blyth key chains and Veda

Pierce car mats, but if many have forgotten her reputation as one of the best

actresses of her generation—and she was clearly regarded as such by her peers

and the industry in the late 1940s and early 1950s—then we have also forgotten

about her name and face in popular culture as a star. This lofty place was undeniably due to her

exquisite beauty, for the only thing more prized in Hollywood than talent is

being photogenic.

I would compare Ann’s introspective, working from the

inside-out skill as an interpretive actress similar to two other actresses slightly

older than she: Teresa Wright and Dorothy McGuire, who both conveyed a soulful

depth to their characters. Neither of

those two tremendously talented, and very serious actresses, who cared more for

their art than for stardom, could reach the power (or were offered the

opportunity) of Ann’s evil Veda Pierce, her venial coquetry of Regina Hubbard,

or her sleazy-cum-brokenhearted and ultimately reformed characters she played

in Swell Guy and A Woman’s Vengeance. And

neither of them sang. Ann was a most valuable

player.

Also, unlike those two ladies, Ann actually was as much a

“star” as a dedicated actress, who, despite pursuing her purposeful private

life with unruffled determination, still seemed to enjoy being a movie star and

attending industry functions, cooperative with the publicity department and whatever the studio asked of her. You can rub elbows with her on the TCM Classic Cruise in two weeks.

She never

shirked autograph hounds, but patiently tackled every slip of paper that was

shoved in front of her, leaving that bold, elegant signature that, like her

beliefs, her manners, and her sense of responsibility, never wavered.

But, though we might dispense with souvenir kitsch, we also are

left a surprisingly scant discography.

Music is a marketable product that lifts the soul and does not just

collect dust. This woman was a beautiful

singer, with a trained voice, but where are all the albums? Celebrities who could sing cranked them out,

and those who could not sing still unaccountably found themselves with record

deals. To my knowledge, Ann had made few records. I have read of her

intention to make albums, particularly a collection of Irish songs, and including

at least one with her brother-in-law, Dennis Day. Do they exist?

At the 32nd Academy

Awards held on April 4, 1960, Ann Blyth accepted the Oscar® for Documentary

Short Subject won by Bert Haanstra for Glass

(which I’ve never seen, but even so, I can’t believe it beat out Donald in Mathmagicland, which we covered here. No really, I’m serious. Really.

Stop laughing.)

Mitzi Gaynor handed the statue

to Ann, and for a moment, Ann Blyth fans, and perhaps even herself, had a fleeting

and thrilling vision of the formerly nominated actress (in the Best Supporting

category for Mildred Pierce) to

finally get her due. But Ann herself

slapped down that daydream and remarked, though clearly excited to be holding

the award, “Gee, I guess this is the closest I’ll ever be to getting one.”

Many superb actors and actresses

finished their careers without an Oscar®, but we film buffs remember, most defiantly, who they are. (This clip from the award ceremony is currently on YouTube here. Scroll to

18:00.)

Surely, being overlooked, or even unknown today, doesn’t all boil down to a film career that

lasted only 13 years? Grace Kelly’s career

was even shorter. Audrey Hepburn’s film

appearances stretched over more decades, but she made less films. Though both were Oscar® winners, deservedly so for those winning roles, neither enjoyed the range of roles, or displayed the acting range of Ann

Blyth; neither possessed her powerful lyric soprano (both gamely tried

musicals, but had weak, if pleasant, singing voices); and neither, despite

their obvious radiant beauty, were more

beautiful. But they had long ago reached

icon status and stayed there.

Both gave up films—for long periods or forever—and abandoned

Hollywood for Europe. Ann never walked

away from her career, she only modified it to her personal tastes and her

family’s needs. (And her home, for

decades, remained in North Hollywood, only a few miles from the studios.)

Is her forgotten status due, perhaps, to a combination of

circumstances unique to Hollywood—that because the quiet stability of her

private life did not make headlines she therefore couldn’t be exploited for profit, because

the bulk of her films are hardly, if ever, shown today, and because, unlike

those tragic stars who died young, or younger, she outlived all her co-stars?

Had she done more television, she might have regained

recognition among younger audiences. (For instance, like Angela Lansbury, who without Murder She Wrote might be known only to classic film buffs and theatre fans, but not have household name recognition in the U.S. and around the world.)

Still, though her staunch fans might mourn her lack of icon status, I doubt Ann

would. Truly, she got the best of the

bargain in a rich and rewarding private life—long and happy marriage, five children,

ten grandchildren, life-long friends in and out of the entertainment industry,

charitable work—and satisfying career in proportions she could deal with, and

never expressed regret.

Have a look at the two videos below at the wedding of the year where the movie star becomes a bride.

Have a look at the two videos below at the wedding of the year where the movie star becomes a bride.

The wedding and reception footage begins in this second video at 1:38. Before that we have a glimpse of Stanwyck on location. This shutterbug really got around.

We have a few more TV appearances to discuss the rest of

this month, and then a few more films to round out the series in the coming weeks that demonstrate a variety of genres: a

western, a war picture, a bio-pic, musicals…and a look at her “third act”

career—as a singer in concerts and nightclubs.

Come back next week to 1979, when Ann and fellow Hollywood star Don

Ameche come under scrutiny in a murder only Jack Klugman can solve in an

episode of Quincy, M.E.

My thanks to the gang at the Classic Movie Blog Association for voting this Year of Ann Blyth series as the Best Movie Series for 2014. Congratulations to all the winners and

nominees in all categories.

And congratulations to the three winners of my recent Goodreads Giveaway, who will each receive a paperback copy of my book on classic films: Movies in Our Time - Hollywood Mirrors and Mimics the Twentieth Century.

***************************

CriticalPast.com

Hartford Courant, July 9, 1950, Part II, page 15, syndicated UP article.

Hartford Courant, July 9, 1950, Part II, page 15, syndicated UP article.

***************************

As most of you probably know by now, this year's TCM Classic Cruise will set sail (proverbially) in October, and one of the celebrity guests is Ann Blyth.

Ann will be doing a couple hour-long conversation sessions, and will also be on hand for a screening of Mildred Pierce.

Have a look here for the rest of the schedule and events with the other celebrity guests. Unfortunately, the cruise is booked, so if' you're late, you can try for the waiting list.

I, sadly, am unable to attend this cruise, but if any reader is going, I invite you (beg you) to share your experiences and/or photos relating to Miss Blyth on this blog as part of our year-long series on her career. I'd really appreciate your perspective on the event, to be our eyes and ears. Thanks.

****************************

THANK YOU....to the following folks whose aid in gathering material for this series has been invaluable: EBH; Kevin Deany of Kevin's Movie Corner; Gerry Szymski of Westmont Movie Classics, Westmont, Illinois; and Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. of Thrilling Days of Yesteryear. And thanks to all those who signed on as backers to my recent Kickstarter campaign. The effort failed to raise the funding needed, but I'll always remember your kind support.

***************************

TRIVIA QUESTION: I've recently been contacted by someone who wants to know if the piano player in Dillinger (1945-see post here) is the boogie-woogie artist Albert Ammons. Please leave comment or drop me a line if you know.

****************************

UPDATE: This series on Ann Blyth is now a book - ANN BLYTH: ACTRESS. SINGER. STAR. -

Also in paperback and eBook from Amazon, CreateSpace, and my Etsy shop: LynchTwinsPublishing.

"Lynch’s book is organized and well-written – and has plenty of amusing observations – but when it comes to describing Blyth’s movies, Lynch’s writing sparkles." - Ruth Kerr, Silver Screenings

"Jacqueline T. Lynch creates a poignant and thoroughly-researched mosaic of memories of a fine, upstanding human being who also happens to be a legendary entertainer." - Deborah Thomas, Java's Journey

"One of the great strengths of Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. is that Lynch not only gives an excellent overview of Blyth's career -- she offers detailed analyses of each of Blyth's roles -- but she puts them in the context of the larger issues of the day."- Amanda Garrett, Old Hollywood Films

"Jacqueline's book will hopefully cause many more people to take a look at this multitalented woman whose career encompassed just about every possible aspect of 20th Century entertainment." - Laura Grieve, Laura's Miscellaneous Musings''

"Jacqueline T. Lynch’s Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. is an extremely well researched undertaking that is a must for all Blyth fans." - Annette Bochenek, Hometowns to Hollywood

Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star.

by Jacqueline T. Lynch

The first book on the career of actress Ann Blyth. Multitalented and remarkably versatile, Blyth began on radio as a child, appeared on Broadway at the age of twelve in Lillian Hellman's Watch on the Rhine, and enjoyed a long and diverse career in films, theatre, television, and concerts. A sensitive dramatic actress, the youngest at the time to be nominated for her role in Mildred Pierce (1945), she also displayed a gift for comedy, and was especially endeared to fans for her expressive and exquisite lyric soprano, which was showcased in many film and stage musicals. Still a popular guest at film festivals, lovely Ms. Blyth remains a treasure of the Hollywood's golden age.

UPDATE: This series on Ann Blyth is now a book - ANN BLYTH: ACTRESS. SINGER. STAR. -

*********************

The audio book for Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. is now for sale on Audible.com, and on Amazon and iTunes.

The audio book for Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. is now for sale on Audible.com, and on Amazon and iTunes.

Also in paperback and eBook from Amazon, CreateSpace, and my Etsy shop: LynchTwinsPublishing.

"Lynch’s book is organized and well-written – and has plenty of amusing observations – but when it comes to describing Blyth’s movies, Lynch’s writing sparkles." - Ruth Kerr, Silver Screenings

"Jacqueline T. Lynch creates a poignant and thoroughly-researched mosaic of memories of a fine, upstanding human being who also happens to be a legendary entertainer." - Deborah Thomas, Java's Journey

"One of the great strengths of Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. is that Lynch not only gives an excellent overview of Blyth's career -- she offers detailed analyses of each of Blyth's roles -- but she puts them in the context of the larger issues of the day."- Amanda Garrett, Old Hollywood Films

"Jacqueline's book will hopefully cause many more people to take a look at this multitalented woman whose career encompassed just about every possible aspect of 20th Century entertainment." - Laura Grieve, Laura's Miscellaneous Musings''

"Jacqueline T. Lynch’s Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. is an extremely well researched undertaking that is a must for all Blyth fans." - Annette Bochenek, Hometowns to Hollywood

Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star.

by Jacqueline T. Lynch

The first book on the career of actress Ann Blyth. Multitalented and remarkably versatile, Blyth began on radio as a child, appeared on Broadway at the age of twelve in Lillian Hellman's Watch on the Rhine, and enjoyed a long and diverse career in films, theatre, television, and concerts. A sensitive dramatic actress, the youngest at the time to be nominated for her role in Mildred Pierce (1945), she also displayed a gift for comedy, and was especially endeared to fans for her expressive and exquisite lyric soprano, which was showcased in many film and stage musicals. Still a popular guest at film festivals, lovely Ms. Blyth remains a treasure of the Hollywood's golden age.

***************************

A new collection of essays, some old, some new, from this blog titled Movies in Our Time: Hollywood Mimics and Mirrors the 20th Century is now out in eBook, and in paperback here.