Remember the Night (1940) is a polar opposite to

My Reputation (1946), covered here in Monday’s post. The latter film feels darker in tone and in cinematography. It featured flashes of noir. The characters were well-to-do upper crust. It was wartime. Conversely,

Remember the Night brings us out of the Depression, among simpler, homespun people. It is screwball comedy when it’s not frankly sentimental, and is a much lighter film in tone as well as on the set. The linchpin between the two movies is Barbara Stanwyck, who with ease can be either a shy upper class widow, or a petty thief from the streets.

There’s a lot to recommend the film, the Preston Sturges script with its absurdities, Fred MacMurray’s average-joe-as-hero, and especially Beulah Bondi. She played mothers most often, and she had a transcendent quality on screen, at the same time utterly realistic. She had this in common with Barbara Stanwyck. The emotional electricity each was able to bring to her work is even greater in their scenes together.

Because Miss Bondi played mothers so often, and was so recognizable a character actress, and had that trademark quiver to her voice, it might be easy to dismiss her, unless you watch her carefully. Especially those large, expressive eyes. Her years of stage work (she came to the movies in her early 40s) shows in her ability to play off her scene partner rather than the camera -- which is what a lot of movie stars did who did not have theater experience. Spring Byington, who also had a career of playing mothers, had a lighter, more comic touch, and she could be accused of sometimes playing a stereotype. That’s because comedy is often born of parody.

But Beulah Bondi is entirely genuine. You see her in this film and recognize the mother she is supposed to be, fluttering in the kitchen and fussing over her son. She is a woman of hard work, restlessness, tension. She snaps at the hired boy. She bends over backwards to make the stranger Barbara Stanwyck welcome in her home, and when her son Fred MacMurray plays the piano and sings the wrong line in “Suwannee River,” she mouths the correct word and shakes her head with disapproval, not angry, but embarrassed that her boy and his fourteen dollars' worth of piano lessons has let her down in front of company, all the while adoring him at the same time.

You have the sense that she has lived a very hard life, but managed to keep a good outlook in spite of it.

Preston Sturges reportedly was not entirely happy with the film. He felt that his screwball comedy was turned into sentimental schmaltz, and at times it was. But

Remember the Night has become for us, in a more cynical era, a wonderful holiday tradition. It could not be so without the sentiment. That it is equal parts screwball only makes it better.

We are coming out of the Depression in 1940. The war is going on in Europe and Asia, but you’d never know it from this movie. When Stanwyck and MacMurray travel cross-country by car, they encounter a WPA sign announcing yet another road construction project -- that never seems to be completed. But it was such projects that helped to drag us out of the depths of the Depression some seven years earlier.

Barbara Stanwyck has her own way of dealing with hard times. She’s a thief, and has walked out of a jewelry store with a diamond bracelet on her arm. She’s caught, and Fred MacMurray is the prosecutor in court.

Her defense attorney, played by Willard Robertson (who had really been a lawyer in younger days), engages in some magnificent and utterly pompous courtroom theatrics, which much have been a blast for him. He contends she was hypnotized by the sparkle in the jewels and forgot what she was doing, which in apparently modern medical terms is called schizophrenia. Yeah, sure it is. He makes P.T. Barnum look like a Presbyterian minister.

The case, which is tried on Christmas Eve, is postponed until early January. Since she has no money and can’t raise bail, she’s doomed to spend Christmas in the hoosegow. Good guy Fred feels bad, and pays Fat Mike the bail bondsmen to get her out for the holiday.

He thinks his good Samaritan deed ends there, but it does not. Oh, but it’s a tricky world full of people with dirty minds. Such is the case with Fat Mike, who thinks Fred wanted Miss Stanwyck free so he can receive sexual favors. (“He’s got a mind like a sewer,” Fred says.) When Fat Mike drags her to Fred’s apartment, she thinks the same.

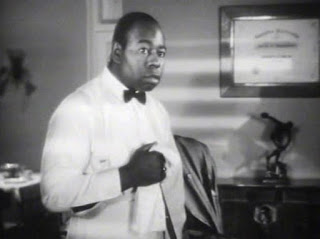

Fred “Snowflake” Toones is Mr. MacMurray’s dimwitted houseman, not a great role but unfortunately typical leavings for Snowflake. His role as a cowboy in Gene Autry’s

The Singing Cowboy discussed here was better.

Snowflake’s packing up Fred’s stuff and trying to hustle him out of the apartment because Fred’s supposed to drive to Indiana to visit his mother for Christmas. Stumped with what to do with Stanwyck, who is more amused than relieved that he has no designs on her, Fred takes her to a supper club for a bite to eat while they figure out where she can go.

He requests the orchestra play “Back Home Again in Indiana” and she and Fred dance to the really lovely rendition by a female vocalist unknown to me, backed by a male quartet. Stanwyck is also from Indiana, and the thought that she might be lying when she announces this is quickly dismissed by her excitement. Barbara Stanwyck really owned a scene and could make you believe anything.

It has been years since she’s seen her mother -- she ran away when a teen -- and Fred suggests he drop her off at her mother’s house for the holiday and pick her up on the drive back. She’s flustered by the idea, and there is a wondrous expression, anxiety mixed with longing, in her dark eyes.

I guess songs about our home states do that to us. Look how Jean Arthur completely lost it during her tipsy rendition of “The Iowa Corn Song” in

A Foreign Affair, discussed here.

Doah! You can just sense a future trivia post about state songs in the movies, can’t you? This stream of consciousness writing is going to be the end of me one of these days.

I’m pretty sure “All Hail to Massachusetts” has never been in a movie.

Mr. MacMurray and Miss Stanwyck take the car across a handful of states without any national highway system at all -- that didn’t come until the 1950s -- and study the paper map when they get lost. See how much fun life was before GPS? I admit, I’m still a map person. I got a kick out of the scene where they have to pull up to a general store/post office to read the name of the town on the building so they can find out where they are.

I was on a train once, traveling through a dark upper New York State night, when, half asleep in my berth, I felt the train stop. I looked out the window to read the name off the train depot to see where we were, but we had not stopped at a depot. All was dark. All except a distant enormous red KODAK in block letters. Ah, I thought to myself. Rochester.

GPS? I spit on your GPS.

However, much as I admire the freewheeling adventure of our two travelers, I am invariably made freezing when I watch this movie because they travel for hundreds of miles in the winter with their car windows rolled down. Now, I know this was filmed on a nice toasty Hollywood soundstage, but jeez-louise. I have driven short distances with no heat and it’s a challenge to the soul. Several hundred miles would be a feat, I fear, beyond my endurance. You see, we here in the northern climes do not go to the trouble and expense of heating our homes for the ambience. We do it to keep from dying. Hypothermia also occurs in cars driving 700-plus miles in freezing temperatures with the windows open.

Especially when they get lost, tired, and decide to sleep in the car. With the windows open.

It’s a cozy shot as they wake up to a cow’s big old face in their faces. At least the cow had a nice warm barn full of other cows in which to spend the night.

The farmer hauls them before the local judge for trespassing and destruction of property, and when they flee justice and become fugitives, MacMurray gets a taste of what life has been like for Stanwyck -- always ducking, living by her wits, and even enjoying the taste of rebellion

The visit at Stanwyck’s mother’s house brings the merriment to a screeching halt and explains why she came to a wayward end. It’s a good set-up scene where she and MacMurray stand on the steps of the home of her mother and stepfather. They rap at the door and hear dogs barking, and then a light goes on. We see her mother only as an eerie dark figure, lit from behind. When we first see her stony face, we can appreciate Stanwyck’s nervousness.

Her mother, a cold, hard woman, well played by Georgia Caine, revives old complaints and resentments against her daughter, who never measured up to her rigid standards. Fred gets Barbara out of there in a most gallant way, and takes her to spend Christmas with his family.

It’s a different story at his mom’s house. Here the idealized home and hearth kicks any rebellion out of Stanwyck and she is transformed by the kindness shown her, and by the gentleness of these country kinfolk. Along with Mother Bondi, Elizabeth Patterson (another stage-trained actress you might remember as Mrs. Trumbull on

I Love Lucy) plays Fred’s spinster aunt.

The mop-haired Sterling Holloway plays the dimwitted hired boy, Willie. You may still think of the voice of Winnie the Pooh when you hear him. We get to hear his mellow tenor on the old chestnut, “A Perfect Day.”

They do all the things Stanwyck would roll her eyes over and ridicule with a cutting remark if she were telling the story, but she’s not telling it. She’s living it, and we see her shy disbelief, almost as if she senses she’s entered a happy Twilight Zone. When Fred plays the piano, we see Stanwyck sitting very still, but rolling her eyes over Fred, and the room where the ladies and Willie are an audience as they string a popcorn chain for the tree. Stanwyck is drinking in the scene around her, like a person removed from it, but astounded to discover she is really part of it.

This still, silent, powerful acting is reprised when she is taken to her room. After Miss Bondi has left her alone, Stanwyck leans over her suitcase on the bed and sinks her chin into her shoulder, looking all around the room pensively, curiously, with almost a note of humor we think, until we see there are tears in her eyes.

Fred, being a square shooter, tells his mother what kind of person Stanwyck really is, and Beulah Bondi, the forgiving type, makes being extra nice to Barbara her new project. This includes gift giving the next morning around the tree. Stanwyck is part of the family by the end of the week.

A cute scene that again, turns unexpectedly tender, when Aunt Elizabeth Patterson hog-ties Stanwyck into a corset (having fun with the Scarlett O’Hara scene of a year before?), and lets her wear a long gown of what was supposed to be part of her own wedding trousseau. We see a stack of letters tied with a ribbon packed away with the dress, and we see that the spinster aunt has been disappointed in love.

Barbara spent New Year’s Eve in a fancy big city hotel ballroom in

My Reputation. Here it’s a barn dance, and when the band leader/square dance caller checks his pocket watch and sees that it’s midnight, the fiddlers and such launch into “Auld Lang Syne” with the best of them, and paper streamers float down from the hayloft.

I love how Sterling Holloway leaps into the arms of a very tall girl to get his kiss.

Mother Bondi sees the attraction between her boy and the petty thief houseguest, whose romance is egged on by her Cupid-playing sister. She tries to gently put a stop to what might be the end of her good boy’s career if he gets tangled up with a bad girl.

It’s a good scene when she levels with Stanwyck. Barbara is first embarrassed that Beulah Bondi knows the truth about her. Stanwyck, always on the ball, gets the message and reassures Miss Bondi. Look at the shot where Bondi stands behind Stanwyck, who stands at her mirror. Stanwyck conveys with a comb touched, as if frozen there, to her cheek, her awkwardness, her shame, and her sorrow to find that she really has no future. Not with Fred, not with any nice guy. Bondi leans over her with a hug, equally agonized.

One the ride home they drive through Canada.

I know they joked about not wanting to drive through Pennsylvania again because that’s where they took it on the lam from the farmer with the shotgun and the judge, but really? That’s a heck of a detour to make. Through a much colder country. Lake-effect snow. With the car windows rolled down.

Nice shot of them by icy Niagara Falls though. We talked about

Niagara Falls in the movies in this previous post. And a lovely ambiguous remark by Stanwyck when MacMurray, who wants to marry her says he’ll take her to Niagara Falls on their honeymoon.

“But we’re there now, Darling.”

Fade to black. Quick, before the censors find out what she means.

Of course, another reason for Canada is that Fred suggests since they are out of the U.S., she could jump bail and he practically invites her to become a fugitive. She wants to go back and face the music. Then when the trial resumes, he tries to throw it, but she won’t let him to that, either. She pleads guilty.

We don’t know what her sentence is going to be, but they’re both pretty sure they won’t be seeing each other for a while. We’re also pretty sure Fred will wait for her.

“Will you stand beside me and hold my hand when they sentence me?” Barbara asks, and again, it is a kind of Christmas miracle that we believe her helpless anxiety, this woman who could be so tough in other movies.

Christmas is a lovely illusion, and is probably best appreciated when we let it be. Reality is for January.

Barbara Stanwyck, Fred MacMurray, Beulah Bondi, and Sterling Holloway reprised their roles in the

Lux Radio Theater presentation of this movie March 25, 1940.

Have a listen here at the Internet Archive, now in public domain, or download it free to your computer. Scroll down to “Remember the Night.”

Merry Christmas, Happy Chanukah, and may the peace of the season be yours.