Richard LaGrand made his film debut in 1943 when Gildersleeve’s Bad Day (1943) was released a couple of months before his 61st birthday. This age is not usually the time of life most of us are allowed to embark on a new career, or even a new facet of our careers, but Hollywood, despite its penchant for youth and glamor, did provide opportunities for elders, even newcomers who were elders, that other fields did not.

This is my contribution to the Classic Movie Blog

Association’s “Screen Debuts and Last Hurrah’s Blogathon.” Have a look here at some swell participating blogs.

Mr. LaGrand may have been a newbie to film, but he started his acting career in 1901. The trope

event occurred that, as a stagehand, he was called upon to perform when an

actor didn’t show – and LaGrand apparently never looked back. He trod the boards in theater, tent shows,

and vaudeville for decades, playing character parts and learning many dialects,

which would help him later on when he entered radio.

He was introduced to radio in 1928 or 1929, depending on the

source, playing Professor Knicklebine in a program called School Days at

the age of 47. Radio was fertile ground

in the 1930s and 1940s for actors, stars as well as character players, but

especially welcome to those players who, as the snarky saying went at the time,

“had a face for radio.” It was a highly

creative form of media, and in calling upon the imaginations of its listeners,

allowed for writing and scenarios where the sky was the limit even on a limited

budget. The storytelling on radio was

often glorious, a boon not only to actors but to writers.

In 1942, Mr. LeGrand landed a radio role for which he would

be known and beloved, pharmacist Mr. Peavey on The Great Gildersleeve.

The character of Throckmorton P. Gildersleeve began on the

popular Fibber McGee and Molly show, and was given his own show in a new

scenario in a new town with niece Marjorie and nephew Leroy (played by the

incomparable Walter Tetley – see this previous post), and wonderful Lillian Randolph as their cook and housekeeper Birdie Lee Coggins (see this previous post). Though Gildersleeve, played at

this time by Harold Peary (later on by Willard Waterman) was a larger-than-life

character, in no way did he outshine the supporting players, which also

included several people in town, Mr. Peavey foremost among them. It seemed as

if just about every day Gildersleeve or his family had to stop in the drug

store for something, engaging the mild-mannered pharmacist in conversation. Openings were always left for Peavey’s

trademark vacillating response, “Well now, I wouldn’t say that.”

Radio programs were such popular entertainment that,

invariably, Hollywood plucked certain personalities for the screen, and

sometimes, would lift the program itself out of the airwaves to the big screen

in an attempt to lure its fans into the theaters. This happened, film buffs and old time radio

buffs may agree, with varying degrees of success. Radio, after all, was not just a story

without pictures. There were plenty of

pictures; they were just in one’s mind.

The unique media did not always transfer well to the big screen.

Gildersleeve’s Bad Day (1943), in which Richard LaGrand had his screen debut, (actually, we have a two-for here: Barbara Hale—future Della Street to Perry Mason also made her screen debut as one of Marge’s friends) was actually the second in a series of four Gildersleeve B-movies, each lasting a little over an hour long and featuring many of the radio show’s characters, but not always the same actors who played them on radio. The most obvious to come to mind would be Walter Tetley, who could not repeat his lively little Leroy on film because Tetley was not a child; he was a grown man, despite the quality of his voice. Niece Marjorie and Judge Horace Hooker are played by different actors as well. There is a loss of chemistry between these characters as a result, they really don’t seem to be the same characters we know from radio. Also, the setting of Gildersleeve’s home might not appear the same way on screen as one imagines it. It doesn’t for me.

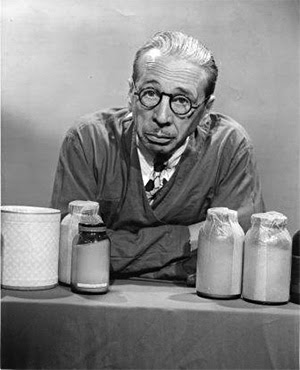

I think the only really familiar setting, to me, in this movie is Peavey’s drug store, and that may be because a lot of drug stores of the era looked pretty similar, so there was no going wrong with a lunch counter and fairly small shop with a back wall with shelves of products and nostrums. Most especially familiar is Mr. Peavey standing behind the counter, slightly hunched, speaking in his careful, nasal-toned speech, always willing to make observations but with a gentlemanly hesitancy to offer a definite opinion, lest he offend. He sometimes muttered wry amusing comments in which he cracked himself up.

In the radio show, he is Richard Peavey (married to “Mrs. Peavey,” whom he always refers to as “Mrs. Peavey”) but the movie calls him J. W. Peavey, for no apparent reason. The plot is contrived and slapstick, and enjoyable for its ridiculousness and quick pace. Gildersleeve, Mr. Peavey, and several other men in town are subpoenaed to sit on a jury in a case involving a local gangster. While the other men in town regret being plucked from their daily lives to sit on a jury, Gildersleeve relishes in it. With his childlike pomposity, he thinks he has been chosen in deference to his superior intellect, and he quickly tries to take center stage, as he usually does on any occasion, even arguing from the jury box as if he is a defense attorney. He is the lone vote holding out when it is time for the jury to deliberate, and with limited facilities to keep the jury sequestered in town, all the men are brought to Gildersleeve’s home to sleep overnight, watched by the bailiff.

Gildy gets into some trouble with the gangsters, and the law

as well when it looks like he has stolen money from Judge Hooker’s safe, but

all comes right, and Peavey gets the last word.

As Gildy is recovering in a hospital bed, he implores his friends to

believe his side of the story, and turns to his old buddy. “You believe me, don’t you, Peavey?”

To which Mr. Peavey, of course, replies, “Well now, I wouldn’t say that.”

The popularity of Mr. Peavey can be attested to his taking a more prominent role in the next movie in the series, Gildersleeve on Broadway (1943), in which Peavey takes Gildersleeve to New York to help him convince a wealthy drug company owner (Big Pharma being represented in this case by dotty Billie Burke) to renew a contract with the druggists at their druggists’ convention. Gildy also wants to spy on Marjorie’s boyfriend, thinking he might be a playboy. Taking the characters out of their hometown of Summerfield actually helps the movie, since we have no familiar settings to compare to the ones already in our imagination.

Particularly enjoyable in this romp is the cameo by Walter Tetley as a bell hop, who with his Brooklynese speech sounds more like his smart aleck character on the Phil Harris and Alice Faye Show rather than Leroy. Mr. Peavey comes off as less befuddled in this movie, more decisive, and his efforts to keep Gildy out of trouble include dressing in drag to pretend to be Gildy’s wife in order to discourage Bille Burke from forcing Gildersleeve to marry her. He’s a hoot. At one point, the butler at a party Peavey tries to crash in drag mistakes Peavey, who has announced he is Mrs. Gildersleeve, for Gildy’s mother. Insulted, Peavey mutters, “Why that old stuffed shirt, I make a better looking women than he does a man.”

Another scene has them, both in male dress, dancing together

as Gildy tries to cut in on Peavey at a party to get him alone to ask his

help. They dance divinely and in all

seriousness, carrying on their conversation.

When Gildy returns Peavey to his partner and politely thanks him for the

dance, Peavey’s lady friend remarks sarcastically, “You boys dance well

together. Does that happen often where

you come from?”

Peavey replies, of course, “Well, I wouldn’t say that.”

Richard LaGrand’s ultimate success with the character of

Richard Peavey may be proven with a special tribute to him at the end of one

particular episode of the radio program.

In “Peavey’s Day Off,” broadcast February 7, 1951, star Harold Peary announces

a special guest, Mr. George Q. Baird, who, on behalf of the National

Association of Retail Druggists, presents LaGrand a scroll signed by 50,000

druggists all over the country congratulating him on 50 years as an actor and

conferring upon him the title “America’s Favorite Neighborhood Druggist.”

The Great Gildersleeve also enjoyed one season as a

television program in 1955-56, but the juggernaut radio show kept going until

1958. Richard LaGrand passed in 1963 at

the age of 80. His film debut may have

been more of a lark than a fruitful opportunity—his total filmography counts

four short movies—but for a man who worked more than half a century as an

actor, national recognition for playing a character so beloved must have been

sweet.

Have a look at the other great blogs participating in CMBA’s

“Screen Debuts and Last Hurrah’s Blogathon.”

Our greatest gift from the Greatest Generation was freedom from fascism. Relive, and celebrate, how evil was faced, discussed, dramatized...and fought. Classic films were Hollywood's weapon.

Get your copy of my book Hollywood Fights Fascism here at Amazon in print or eBook, or FREE here for a limited time at Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, and a variety of other online shops.

Jacqueline T. Lynch is the author of Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. and Movies in Our Time - Hollywood Mirrors and Mimics the Twentieth Century and Hollywood Fights Fascism and Christmas in Classic Films. TO JOIN HER READERS' GROUP - follow this link for a free book as a thank-you for joining.

4 comments:

What a fantastic story. I know nothing about The Great Gildersleeve, but I love those old time vaudeville, theater and radio characters. They we professionals down to their tippy toes. Thanks for an informative and enjoyable post.

Thank you! Yes, I love the old-timers.

I'm a sucker for The Great Gildersleeve radio show, but didn't realize they made Gildersleeve films. I'll be keeping an eye out for them!

You can actually catch them on YouTube, several of them at least, if not all. They're fun.

Post a Comment