We interrupt our regularly scheduled blog post.

In answer to Moira Finnie’s call for imaginary film noir dream casts (see her post at Skeins of Thought), and because I can’t refuse a double-dog dare, here is a film that should have been made, but for studio politics, or the Code, or maybe just nobody got around to it. The cast and crew are assembled without regard to studio affiliation, like a dream team, if you will.

“Dead Men Need a Plot.”

The time: 1949. The place: Los Angeles. It is raining. It rains the entire movie. There is a severe trench coat shortage. Things couldn’t get more bleak. Well, yes, they could.

Charles Lane - Perennial character actor playing scowling sour types for all of five minutes of screen time in a million movies, for once in his life, gets to play the lead. He is a private investigator on the hunt for his missing partner, played by…

Humphrey Bogart - who, for once in his life, plays a happy go lucky schmuck for all of about five minutes of screen time. His name is Clarence and his socks don’t match.

Barbara Stanwyck is his sister, Inez De Valencia, who arranged to have brother Bogey kidnapped for his own good, because he knew too much, until the heat is off, until his memory comes back, until it stops raining. Her name, like the blonde wig, is fake. She liked the sound of it. She used to have a cat by that name. Then the cat died.

Stanwyck is crazy in love with Charles Lane. Who wouldn’t be? That nasal twang and those glasses! But she has competition. Lizabeth Scott, Ruth Roman, and Lauren Bacall are society dames all with secrets only Bogie knows, and all not so secretly harboring passionate desire for Charles Lane, perhaps even enough to kill for him. (In the 1977 parody/remake written by Neil Simon, “Only Funny If You’ve Seen the Original So You Get the Jokes”, Lauren Bacall’s part is played even better by Eileen Brennan.)

James Gleason plays the hard-boiled police detective with seasonal allergies and a grudge against Charles Lane.

Regis Toomey is his desk sergeant with the sick mother, played by Ethel Barrymore, who accidentally shoots Toomey when he tiptoes into her room to check on her. Charles Lane happens upon the scene shortly afterward, and gets pinned for the murder. Nobody would believe Ethel Barrymore would shoot anybody, even though we hear she’s done that sort of thing before.

Dana Andrews and Arthur Kennedy are bitter war veterans, one of whom is engaged to Ruth Roman, but they can’t remember which one, so they duke it out in the waterfront bar where Bogey is being held in the basement under heavy sedation, “Liebesträume” played over and over again on a nearby upright piano by…

Van Heflin, a drifter who took the job only because he needed the money and was out of cigarettes.

On the lam from James Gleason, Charles Lane enters the bar, gets hit with a blackjack for the 47th time, and, over the noise of the fistfight, as he regains consciousness hears dimly the strains of “Liebesträume” coming up from the floorboards, which of course leads him right to Bogey.

Stanwyck has a great scene here where she pleads with Charles Lane to leave Bogey safely where he is, so that she and Charles Lane can be married. Charles Lane has no idea what she’s talking about, but isn’t surprised she’s in love with him, because he’s, well, Charles Lane. He gives her the brush off in his utterly macho Charles Lane way, and she pulls out a bullwhip. Heflin segues into a spirited rendition of “Mule Train” when Stanwyck’s whip snapping sends the astonished Charles Lane sprawling over Van Heflin’s piano. Heflin quits on the spot.

Bogey comes out of his stupor. Stanwyck crawls out the cellar window, not easy in beaded crepe de Chine, leaps onto a horse in the alley and rides off. The whole thing nearly turns into a western, but for the quick thinking of cinematographer, Gregg Toland, who pulls off a remarkable shot where we can see the retreating Stanwyck galloping down Sunset Boulevard in the distance, and the extreme close-up on her husband’s service revolver in the gloved hand of the late-arriving Ruth Roman (who has thrown over whichever of the bitter war vets is her husband for Charles Lane) at the same time. The dizzying effect makes our eyes hurt and we are diverted away from all thoughts of westerns.

Look for a cameo appearance by Alfred Hitchcock as the man at the bar trying unsuccessfully to tell a funny story. Odd for Hitchcock to have a cameo, because he didn’t direct this picture. He just showed up at the wrong soundstage, and they put him to work.

Mary Astor also has a brief role as the Crazy Woman with Tuba in the nightclub scene, but she’s uncredited and you have to pause it to really see her standing behind redhaired, gum snaping cigarette girl played by Moira Finnie.

“Dead Men Need a Plot” is directed by Ida Lupino, script is by Raymond Chandler and Olive Higgins Prouty, and several other writers who shortly became blacklisted so of course, we cannot mention their names. They’d probably rather we didn’t.

Anybody else want to try? Grab a cast.

IMPRISON TRAITOR, PEDOPHILE, AND CONVICTED FELON TRUMP.

Thursday, April 30, 2009

Monday, April 27, 2009

Eve Arden

Eve Arden received an honorary membership in the National Education Association in 1952. “Our Miss Brooks” wasn’t real, just a radio sitcom, but Miss Arden’s portrayal of English teacher Connie Brooks was real enough to have actually gotten her teaching offers.

A veteran actress of film over several decades, and an Academy Award nominee in 1945 for “Mildred Pierce”, Eve Arden played the sane and sassy comic foil or dramatic character actress with exquisite precision, with such a strong screen presence that it didn’t matter if she wasn’t the lead. On radio, however, she was the lead and took the ball, and ran with it. It was the perfect medium for her. Nobody could speak like she could, expressing shades of meaning, usually very witty, with only her voice. Her voice made Connie Brooks seem so human, and so real.

Have a listen here for a dramatic turn in the series “Suspense”, scroll down to an episode from January 18, 1951 called “The Well-Dressed Corpse.”

For a turn as Connie Brooks, have a listen here to some of the “Our Miss Brooks” episodes from 1950 on the Internet Archive.

And have a look here at Kate’s recent tribute to Eve Arden on Silents an Talkies.

Thursday, April 23, 2009

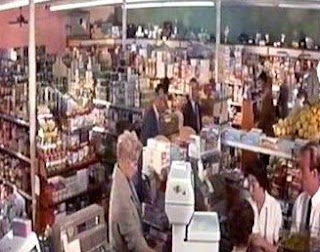

The "Super" Market

Despite this intriguing scene from “Double Indemnity” (1944) (see blog post on the film here) where Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck discuss their nefarious plans in a supermarket, this bastion of American society doesn’t seem to have too great an importance in the films of the 1940s through 1950s, when supermarkets actually were a business idea building momentum to the point they became a social force in a new suburban society.

Jerry’s Market on Los Feliz appears to be one of the very early small, self-service markets, located in urban areas unlike the later suburban freestanding supermarkets with acres of parking lot.

Jerry’s Market on Los Feliz appears to be one of the very early small, self-service markets, located in urban areas unlike the later suburban freestanding supermarkets with acres of parking lot.

By the time we have this scene with Kirk Douglas and Kim Novak from “Strangers When We Meet” (1960) (see blog post on the film here) which, since it takes place in suburbia, a supermarket scene could hardly be avoided, the venerable supermarket had hit its stride. A bit more grand than Fred and Barbara’s hangout, but nothing like the extravaganza SuperStores and Big Box and Bulk Outlets on the horizon for another generation.

The supermarket actually began in the early 1930s by Michael J. Cullen, who opened a barebones enormous self-service grocery store in Queens, New York. The store, and his resulting chain of them, were called King Kullen. Apparently this was the first movie connection with supermarkets, because name was supposed to be a parody of the name King Kong.

Most areas of the US did not really get supermarkets until the 1950s, but heard about their wonders like they might have heard about TV and atomic power long before the advent of these other post-war features of our lives.

Most areas of the US did not really get supermarkets until the 1950s, but heard about their wonders like they might have heard about TV and atomic power long before the advent of these other post-war features of our lives. Another early Hollywood connection to supermarkets comes in the form of this very first Mighty Mouse cartoon. “Mouse of Tomorrow” (1942) pre-dates Mr. MacMurray’s and Miss Stanwyck’s date in the supermarket by two years, and explains the origin of the Mighty Mouse, which had to do with a supermarket.

So new were the idea of self-service markets, that the word “super” used to describe the market sounded terribly new and terribly funny. We don’t even think the word “supermarket” sounds funny today, but in its earliest days, it seemed absurd referring to a grocery store as something “super.”

It is the conjecture of this cartoon that if it is such a “super” market, it must sell “super” products. A mouse, one of many in his little mouse community, is terrorized by nasty cats. He escapes into a supermarket, where shelves piled high with cans tower above the little guy. It is a frightening new world. When he eats the “super” soup and “super cheese” and washes with “super soap”, he is transfored in a “super” mouse, or, Mighty Mouse.

For more on the history of supermarkets and the heyday of the suburban discount stores, have a look at this really fun website: Pleasant Family Shopping. Maybe you’ll recognize your hometown store as it was back when.

Monday, April 20, 2009

El Capitan - Los Angeles

Above is what appears to be little more than an over-the-shoulder glance at the tops of palm trees and the sign for the El Capitan Theatre. Where else could we be but Hollywood Boulevard?

Real estate developer Charles Toberman developed this theater as part of a trio of theaters with Sid Grauman known as the Egyptian, the Chinese, and the El Capitan.

Opened on May 3, 1926, called "Hollywood's First Home of Spoken Drama," the El Capitan began as a theater for live stage shows. That first play was "Charlot's Revue," featuring British stars Jack Buchanan, Gertrude Lawrence, and Beatrice Lillie.

Live theatre was produced here for ten years, and afterward, the El Capitan became a movie theater in this movie-making town. “Citizen Kane” (1941) premiered here. In 1942, the name changed to Hollywood Paramount, and its function to movie house.

In 1989, The Walt Disney Company, with Pacific Theatres restored the El Capitan and it was re-opened in June, 1991.

For more on the El Capitan, have a look at this website.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Now Playing - Father Takes a Wife (1941)

This splashy ad for “Father Takes a Wife” (1941) hails the screen return of Gloria Swanson, who had not done a film in some seven years, and whose next film wouldn’t be for another nine years. But that film-to-be was “Sunset Blvd.”, so it would be worth the wait.

Her cast here in this comedy about an actress who gives up a career for marriage includes the ever dapper Adolphe Menjou, John Howard as his son (who we last saw in “Make Haste to Live”), Desi Arnaz, and more importantly, Mary Treen, who in her string of funny maids, waitresses, secretaries and other lovable plain Janes, was always delightful, occasionally poignant, and often better than her material. She is cast here as a secretary.

Monday, April 13, 2009

The Song of Bernadette (1943)

“The Song of Bernadette” (1943) pits man against miracle in a many-layered universe. The first layer of this complicated universe is the historical 19th century event on which the story is based. Then, there is the book by Franz Werfel and the World War II climate under which that book was written and published. Finally, there is Hollywood, that tries diplomatically to be both pious and frank, spiritual and temporal, to present a money-making story, and yet present it under the auspices of a religious experience.

By filming a story about a miracle, Hollywood created something of a miracle in its own craftsmanship just by what it accomplished and how.

On this Easter Monday, we take a look at Hollywood’s presentation of a miracle and the ironically realistic way it chose to present it. Man is by nature a creature which believes. We have religions and sometimes complicated protocols of faith. We have superstitions, and we have good luck and bad luck, and we have worries and fears and paranoia, and that is all part of what we willingly believe without proof. On the opposite side of man’s nature is an innate skepticism.

Someone who believes in the efficacy of the prayers of his own faith, may disbelieve the efficacy of prayers of another faith. An atheist may disbelieve the efficacy of any prayer at all, and yet wholeheartedly believe in luck, or horoscopes, or that a co-worker who gives him a dirty look is out to get him. It may be the co-worker is just in a bad mood, but that does not shake the belief of the paranoid. A lot of logical, sensible people knock on wood. Even people who believe in nothing believe in something, even if it is only the superiority of their own opinions.

So, we believe, regularly, commonly, without proof. It may be part of our DNA. But at the same time we are skeptical over someone else’s experiences. “The Song of Bernadette” shows these disparate sides of human nature and the clinging onto of human dignity more than it puts forward of one belief over another, or promotes miracles. The film begins with the narrative,

“For those who believe in God, no explanation is necessary. For those who do not believe in God, no explanation is possible.”

But this is not merely a disclaimer to placate a general movie-going audience of mostly Christians, albeit demographically mostly non-Roman Catholics. It is a simple analysis of human nature. Belief and skepticism may be at opposite poles, in life and in this movie, but they do not represent good and bad. There is nothing bad in skepticism. Skepticism is healthy and beneficial, except when it becomes distorted as a tool for manipulation. The same may be said for belief. It is healthy and beneficial, except when it becomes distorted as a tool for manipulation. This film is remarkably and consciously clear in demonstrating that.

It is the telling of the story, and not the miracle, that is the subject of this post. Such care was taken in the historical accuracy of the southern French village (a realistic set of stone which was also used, I believe, for “How Green Was My Valley”?), in the soaring and evocative music by Alfred Newman, in the clothes, the everyday life of the poor-as-dirt peasantry, in the meaty, articulate script, in the camera work which plays on light and dark with such soul-baring intimacy. This film is an example of craftsmanship at its best. Stark, unflinching, and yet remarkably empathetic craftsmanship. The studio, and all those involved evidently wanted to make not just a money-making film, but a great film. So often we have seen so-called blockbuster movies made at this period, and especially today, where a truckload of money is thrown into a project, but what results is only lumbering over-produced garbage. This film shines with the obviously meticulous care put into it.

The cast is a collection of some of the best character actors of the day, along with a flock of extras as villagers, and a young Jennifer Jones in the title role that made her a star, and won her an Academy Award. About the only weak links are the child actors playing her younger siblings, who seem by the way they speak and carry themselves to resemble 20th century American kids rather than 19th Century European children, but the rest of the cast are true and believable.

Anne Revere and Roman Bohnen play the parents of Jennifer Jones’ Bernadette. Miss Revere was commonly cast in hardscrabble mother roles. How much was due to her scrubbed complexion mottled with freckles and her strong jaw and the flint in her eyes that suddenly turned soft and sympathetic can be guessed at. Most actors are chosen for their roles because of their looks, and sometimes their height. Other actresses habitually played mothers on screen, but did not have Miss Revere’s quality of appearing genuine. Other screen mothers were often only superficially mothers, the kind who came out of the kitchen with milk and cookies. Revere gives us the impression she actually changed diapers, wiped noses, was the hand that rocked the cradle, and sometimes the backhand to the cheek or slap on the bottom.

Roman Bohnen played Jones’ father, an out-of-work peasant at his wits end, beyond hope and failing strength. He is downtrodden and resentful, petty and frustrated, but we see the depth of his love for his daughter when he desperately promises to let her return to the grotto, after having already forbid it, and when he scrambles fearfully into the Royal Prosecutor’s office, where Jones has been taken for questioning, to claim her and take her home. From the time we see him rise up early to beg for a job dumping hospital waste, to the point where he must say a final goodbye to his daughter, in every action, this man’s heart is breaking.

Charles Bickford is the Dean of Lourdes, the village priest who, in his dashing Cavalier-like hat and cape looks something like a superhero before the ragged villagers. The sash on his cassock is cinched firmly about his waist, making the line of his body look lean and rugged, with broad shoulders and he takes his long strides with a lordly bearing. Mr. Bickford, last seen here as Jane Wyman’s father in “Johnny Belinda” (1948), played tough, commanding men who kept their own counsel, and whose role here as the scornful priest who doubts Bernadette and later becomes her staunchest ally, demonstrates his formidable screen presence.

Vincent Price heads the local magistrates who connive to discredit Bernadette. He is the self-important and dangerously ambitious Royal Prosecutor. It is a role perfect for Mr. Price, whose elegant disdain so completely captures this highly intelligent, highly skeptical man. There is a particular facet about his character that is especially memorable, and that is his constant flourishing of a voluminous handkerchief, dabbing at his nose as he makes a gesture or a point about the foolish Jennifer Jones and the idiot townspeople.

“What do you expect from a peasantry fed on dogmas and superstitious nonsense?”

At times he looks foppish waving the hanky, and at other times, it is as if he is using it to steal scenes, and it becomes an almost funny prop, along with his ever-present allergy symptoms. It is only late in the film we notice with an ominous sense of foreboding that his voice has grown hoarse, and that his raw throat and troublesome sinuses, which he writes off as influenza, is actually a serious illness. Contrasting the lighter earlier scenes of the scene-stealing foppish hanky, it is a shock to learn now he has throat cancer.

Charles Dingle, so delightfully wicked as the rascal older brother in “The Little Foxes” (1941) plays another devious role here as the chief of police, and Lee J. Cobb as the kindly and scrupulously objective village doctor rounds out a very strong supportive cast of town officials.

Gladys Cooper, so impressive here as the envious, bitter nun who first presents as Bernadette’s stern school teacher, and then her mistress of novices in the convent, conducts a master class on acting just in the convent scenes alone when she confronts Jennifer Jones about her supposed sightings of the Lady. Miss Cooper’s dark eyes burn in her wan face, emitting her particular venom for Jones through those eyes. Then a convulsion of emotion rips out of those remarkable eyes as we see Cooper has an epiphany of her own when Jones reveals proof of her agonizing illness that she has borne with quiet patience. Miss Cooper’s character takes a complete turn, and she melts almost like the Wicked Witch of the West, but not from water, from the sickening knowledge of her own deformed reflection in the mirror of her soul.

Jennifer Jones is Bernadette, from every nuance cast in stillness, even from her screen test. It is a famous Hollywood anecdote that among all the actresses trying out for this much-sought-after role and who were told to gaze at a stick held above the camera, Jennifer Jones, according to the director, was the only one who saw the Lady.

We can easily believe it. Her quiet sense of wonder is exquisite in this film. In the scene where she sees the Lady for the first time, there is a really very long moment of her fixated, unblinking stare into a kind of paranormal light cast during the Lady’s presence. In subsequent encounters, Jones’ child-like characterization is so complete that her fascinated gaze reminds one of the way a child will turn, eyes wide and unblinking, to the TV, absolutely absorbed by a toy commercial. If you’ve ever tried to talk to a child when a toy commercial is on, you know how exasperated Bernadette’s parents are when they cannot make her disregard her rapture for the Lady.

But her stillness, her economy of gesture and movement does not keep her from growing as a character, and this is another remarkable aspect to her work in this movie. She begins as a somewhat diffident, frail girl, a poor student who everyone, including herself, refers to as stupid. Her personality enlivens under the presence of the Lady, and we begin to see in her a sense of joy, a sense of wonder, and an occasionally comical common sense.

When questioned by the authorities on her lunatic behavior of pretending to wash herself with dirt, and falling to her knees, eating wild scrub plants like “an animal”, Bernadette replies, “Do you act like an animal when you eat salad?”

It is another Hollywood anecdote that when it came time to film the scene where the Lady asks Bernadette to wash her hands and face in a stream which does not exist, and eat some nearby plants, director Henry King wanted Jones to only pretend. Miss Jones insisted on digging into the ground with her hands, smearing dirt on her face and shoving the weeds into her mouth and eating them.

There was some debate at the time as to whether the film should show an image of the Virgin Mary to whom Bernadette is speaking, or, since nobody but Bernadette saw the vision, to leave it out. There is probably equal logic and merit on both sides, but having the movie-going audience see the vision as Bernadette sees it at least steers the story away from having us, along with the villagers, believe Bernadette is a lunatic. We are then free to focus on the villagers’ and the Church’s skepticism, and not our own.

Nobody believes her, and she is harassed not only by civil authorities, but most especially by the Roman Catholic Church. Even Charles Bickford, the priest who begins by threatening her with a broom and later becomes her protector, never really swallows the story completely. He is at last convinced of her sincerity and her innocence, but to believe that the Virgin would deign to make an appearance in such a lowly, filthy place to such a miserably nobody of a girl, is ridiculous. He is skeptical.

“Christ was born in a stable,” counters Bernadette’s formidable aunt, who chastises her parents for their lack of support and demands that the girl be allowed to visit the makeshift grotto in the town dump. When the spring water that wasn’t there suddenly appears, and a couple of people are healed by washing in it, a horde of people needing to believe in something show up, and keep showing up, and so do the concessionaires. The town prospers in the parasitic cycle of public relations and commerce.

Miss Jones is at last made to understand that through the tumult she has caused, her life can never be the same again. She is offered both sanctuary and grinding servitude in a convent, and we see another aspect of her growing maturity as she says goodbye to the village boy who appears to have a crush on her. There is no fully developed romance between them, but the film intimates that there would be if only Bernadette could be left alone. A sweet, and deeply sad moment, when he stops her carriage with an armload of flowers as she is leaving for the convent, (that appear to be cherry blossoms?) and vows that he, too, will never marry. She snaps off a sprig of pure white blossoms and hands it back to him, and it is almost as if they are blessing each other in a kind of wedding ceremony for a chaste marriage.

When Bernadette arrives at the convent, she meets up with her old nemesis Gladys Cooper, and when that mean little nun walks through the door, we are perhaps even more shocked and depressed about it than Bernadette is. There is another wonderfully still, yet evocative moment, when left in her room alone, her “cell”, Jones glances around with a frozen expression and limpid eyes that gaze with a different, more foreboding sort of wonder. The cell is actually far more clean and comfortable than the home she grew up in, but here we see she is terrifyingly alone. We see a crucifix mounted on the bare whitewashed wall over her shoulder, and we wonder if the Lady has left her all alone forever, too.

We might comment with amusement that the vision of the Lady was actually played by a pregnant Linda Darnell, but that’s been noted so often that I think all of the really clever jokes and remarks have already been made, certainly nothing I can top.

Even here in the convent, Bernadette is still brought before Church commissions, made to testify over and over to what she saw. Even Peter denied Christ three times before the cock crowed, but Bernadette is more steadfast. She insists she saw what she saw. It is not a martyr’s courage that makes her declare this, only her simplicity and a lack of street smarts in knowing how to lie.

At the very end of the film, as Bernadette lay dying, she finally sees her Lady again, who beckons as if coming to her for a hug. Miss Jones once again makes us believe everything in her heart when she calls out to the vision that nobody else sees, “I love you…I love you!”

The musical score, a beautiful piece of art in itself, is suddenly covered by a male voice over at the end with a recitation from the “Song of Solomon”, which I always thought was a rather odd way to the end the movie. It’s one of the more beautiful passages from the Bible, but it never seemed appropriate to me to use here, at least until listening to the bonus track of commentary from the 2003 restoration DVD of this film. It is explained that the composer of the score, Alfred Newman, saw in his mind that the movie was really a love story between Bernadette and her Lady. A sweet way to look at it, and makes the words from the Song of Solomon as Bernadette is being encouraged by the Lady at the end of the film,

“Arise my love, my fair one, and come away….”

seem well used.

A note on this commentary track: we’ve commented before on this blog about how disappointing some DVD commentary tracks are, but this is not one of them. Delivered by historian Donald Spoto, Newman biographer Jon Burlingame, and Jones biographer Edward Z. Epstein, the commentary to this film is truly excellent. Mr. Burlingame covers the towering score by Alfred Newman, Spoto covers the historical setting, and their remarks are scholarly, spoken with clarity and articulate passion, as well as in voices, particularly in Mr. Spoto’s case, that are resonant and pleasing. It’s always enjoyable to hear someone speak well. Mr. Epstein’s comments are more superficial, but if one is unfamiliar with the life and career of Jennifer Jones, he provides a useful background. All three gentlemen’s remarks dovetail neatly.

Bonus tracks aside, the restoration of the film on this DVD (available from Amazon here) is worth the price alone, so vivid and sharp is the visual quality compared to any old television screenings you may have seen in the past.

The commentary underscores the idea that this film represents a many-layered universe, in this case, history and Hollywood. They ruminate on Franz Werfel, a Jew escaping the Nazis who on his escape route discovered the story of Lourdes and wrote a book on Bernadette, who had been canonized as a saint only fairly recently, in 1933. The notice at the very end of the film reminding us to buy war bonds is actually jarring; so deeply have we been sent into the19th century that a reminder of the present is a shock.

The film shows realities of poverty, of religious leaders who dismiss the idea that a sign of heavenly grace can be bestowed on anyone other than themselves, and of civil authorities who are threatened by the raising up of a peasant class until they find their own way to exploit it. These are realities as ancient as mankind, and as current as today’s headlines.

“She’s a religious fanatic, and every time religious fanaticism steps forward, mankind steps backward,” Vincent Price declares in this marvelously literate script. We may agree.

“You should be thankful, Bernadette, you did not live in former times” a spiteful Gladys Cooper tells her with delicious malice, because she would have surely been burned at the stake. Very true.

And Miss Cooper asks the most meaningful, the most fatal question of all, the same question all the clergy and all the authorities, and all the villagers ask quietly to themselves in their most private thoughts,

“Why then should God choose you, not me?”

Bernadette doesn’t have an answer to that one, and 20th Century Fox wisely refrains from providing one, but we don’t really need an answer. The question itself is thought-provoking enough.

Thursday, April 9, 2009

Let My People Go

Cecil B. DeMille’s lavish, lusty spectacle of the story of Moses in two versions of “The Ten Commandments” is not the only movie view we may take in remembrance of Passover. Here is another one.

Our friend Citizen K recently posted this clip on his blog, and so, remorselessly I steal it today. It’s from the 1941 comedy “Sullivan’s Travels”, and though there is much to discuss on this film and its stars Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake at another time, this day is for this scene.

Towards the end of the film, Sullivan has found himself a miserable victim of injustice, bound helplessly to a backwater prison chain gang. In a remote rural church, the minister ends his service and prepares the congregation for a treat, an evening’s entertainment where they are to watch movies, starting off with a cartoon, on a sheet.

The prisoners in the chain gang are their invited guests. We hear the minister remind his flock to welcome the prisoners with compassion, and to take care they not display any attitude of superiority over them, so as not to hurt their feelings. We see the ragged clothes of the congregation, the plain, dim church and its rough wooden benches, and we may wonder how such poverty stricken people need to guard against feelings of superiority. Then the prisoners enter, shuffling in their chains, eyes cast downward, bone-tired and suspicious of any kindness.

The congregation saves the best seats for their guests, and led by the majestic voice of their pastor, the indomitably soulful Jess Lee Brooks, welcomes them with a song whose message cries out over the millennia, a song of enslavement, of seeking relief and justice.

Let my people go.

These descendents of African slaves sing an old song, taken from the ancient story of Jewish slaves, re-worked into one of most famous in the canon of Negro spirituals, and given as a gift to this rag-tag bunch of convicts.

The Jews of the Book of Exodus were freed by a miracle and the tenacity of a prophet. The slave forebears of this congregation were freed by a war, and the legislation it engendered. The convicts will taste a little bit of freedom tonight, laughing at a cartoon.

A rollicking slapstick comedy suddenly stops short, and soberly kisses us on the cheek with a reminder of our own humanity, and our innate human dignity, even in the oddest of the places and the lowliest of circumstances.

It is a magical scene, one of the few in Hollywood's heyday where a simple but powerful message truly transcends race or religion.

A blessed Passover then, to all who commemorate the wait, and the hope, and the blessing, and the freedom.

Monday, April 6, 2009

Donald in Mathmagicland (1959)

“Donald in Mathmagic Land” (1959) makes math beautiful, sings hosannas to the orderliness and sense of logic that is the foundation of beauty in art, in music, in nature, and in human beings.

A tall order, but Donald Duck handles it well.

Here, the irascible Donald is an Everyduck, marching resolutely through the ominous world of equations and square roots, on a journey through time and space to show us the roots of civilization, the beauty in mankind as expressed through math. We even are shown what infinity looks like.

Only in a cartoon can you see what infinity looks like. Some boxes and some squiggles that keep repeating themselves. That’s about it, really.

Live action scenes of flowers, and of the natural world, and of a fellow giving a billiards demonstration according to mathematical logic are mesmerizing. The lulling voice of narrator Paul Frees is also mesmerizing. I raise this 27-minute cartoon for discussion today because of its remarkably quiet and serene exploration of a seemingly mundane subject, math, and turning it into a compelling journey of the mind.

But it’s the lulling and the mesmerizing aspect, above all, that fascinates. It’s a world where everything, from art, to science, to music, to the human body, takes its beauteous form according to logic. Most majestically and most mercifully in an otherwise chaotic world, here…everything…adds…up.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

Smoking Pinsetters

Above we have one of my favorite moments from “Since You Went Away” (1944), when two sarcastic, smoking, female pinsetters make disparaging remarks about Jennifer Jones’ bowling prowess.

“Well, she finally hit one.”

Have a look at the scene where a determined Jennifer Jones attempts a bowling lesson, and you’ll see pinsetters in the far background, behind all the alleys, jumping down at safe moments to retrieve pins.

Along the same lines as our earlier post on slide rules (see here), a category I suppose we could call Stuff We No Longer Do, a live person doing the pin setting is something you see only in the movies these days. It has been quite some time since bowling alley pin setting has been automated, which must have put a lot of sarcastic smoking females out of work. (Have a look here for my post on New England’s bowling game, candlepin bowling, on my New England Travels blog.)

Pin setting was mostly done by boys and young men, but I imagine we have young women doing the job in this film because it was wartime, and lots of formerly male-only jobs were taken over by women. It wasn’t until after the war that a lot of bowling alleys started getting automatic pinsetters.

For more on “Since You Went Away”, not about the bowling, have a look at this earlier blog post from April 2007.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)