A League of Their Own (1992) is the best movie ever

made about baseball. It achieves this by

also being about a lot of other things, and baseball is the conduit by which

all those other things flow together.

Above all, it shows a love for the game that can only be displayed by a

group of people so desperate to be allowed to play it for the joy and sense of

freedom it gives them.

Though this blog is concerned primarily with classic films,

I’ve always been interested in modern-day films set the past, especially with

an eye towards telling the story with the style of classic films: the bold

newspaper headlines, the montage of images to show the passage of time, and the

gimmick of splicing in a few replica newsreel bits. I’m a sucker for it.

This movie, beyond illustrating a period of history,

actually makes history by resurrecting professional women’s baseball in

the 1940s – something many people had forgotten about by 1992 and most did not

know about at all. I can recall reading

a review of the movie at the time it was released by a dismissive reviewer who

had no knowledge of the league and displayed very little appreciation of the

movie because he did not understand the historical background.

A short-lived television series followed, and now on the

movie’s 30th anniversary a new series is being launched next month,

but in between 1992 and now there have been books about the subject, websites

and Facebook pages created, a popular exhibit at the Baseball Hall of Fame, and

merchandise promoting a league that no longer exists – including the iconic

dress (literally, a dress) uniform sold as Halloween costumes. It spawned the motto: “There’s no crying in baseball!”

Director Penny Marshall filled this movie with heart, affection, courage, humor, and that love of baseball. What particularly appeals to me, beyond the really excellent job of sets, costumes, script with topical references, are the smaller moments that represent something huge.

For instance, the African-American woman who catches the

fastball, looks back at stars Geena Davis and Lori Petty with pride, nods, and

walks away. She will not be invited to

play on the All American Girls Professional Baseball League because she is

Black. Here’s a link to the true-life story of how that lady, DeLisa Chinn-Tyler, came to be in that scene. The scene was not in the script. She was a terrific ballplayer, came down to

try out for the movie, and like her character, was not utilized because of her

skin color. But Penny Marshall, with her

great eye for telling a story, put her in this nonspeaking role for only a few moments and left an indelible

impression and told a huge chunk of history while she was at it.

I love that Geena Davis, from the moment her character as an older woman must be prodded by her daughter to attend a reunion of the team, throughout the scenes of her joining the team for her sister’s sake and becoming its reluctant star, shows the awkwardness of many women of the day who, in many fields, feel they must conceal or restrain their talent or their joy in their talent because it is considered inappropriate to be competitive, athletic, to take time for oneself to play, or deserve to be paid for any work formerly done by a man. Moreover, her love for her sister means that even though she nags her and is overprotective, she will not lament dropping the ball in the last scene to make her sister the star. Did she drop it on purpose? We’ll never know, and that is another beauty of the movie.

A League of Their Own (1992) exhibit at the Baseball Hall of Fame displaying the fictional Life magazine cover with star player Dottie on the cover. (photo JT Lynch)

Her daughter, in trying to get her to go to the league

reunion, says, “Mom, when are you going to realize how special it was, how much

it all meant?” By the end of the movie,

we know what it meant, and it seems Dottie does, too.

I love the grown Stilwell, who as a bratty child bedeviled

the team (again, illustrating a situation common to women of that era – their

husbands did not always take over babysitting chores), stands before his

mother’s image on a poster exhibit at the Hall of Fame and we see how much he

misses her. Always makes me tear up. We realize then that Evelyn’s not coming to

the reunion. He says that he had to be there for the exhibit opening because,

“She always said this was the best time she ever had in her whole life.” We may mourn for Evelyn, played by Betty

Schram, as well in the thought that her few years on the team was better than

life at home.

The scenes showing the women having to attend charm school may seem condescending, but I can recall reading at least one memory of a former player who said she liked the classes because she had spent her childhood in poverty, had never been inside a restaurant, and was eager to learn what she was told were the social graces. Remember the character of Shirley, played by Ann Cusak, who cannot read her own name on the roster because she is illiterate, and the girls teach her to read on long trips on the team bus.

Spot on is the radio program of the lady protesting the

formation of a league of female ballplayers, her charge being that it would

make them more masculine. As silly as

this sounds, this was exactly what WACs, WAVEs, SPARS, women Marines and any

female volunteering to help with the war effort faced by society, carefully

chaperoned by a military that needed them but did not want to offend the

public.

We know that Rosie the Riveter, after being lauded for helping win the war, was summarily booted out of the factories when the war was over, and the movie includes a foreshadowing of this when Mr. Lowenstein, played by David Strathairn complains to Mr. Harvey, played by Garry Marshall when Marshall wants to end the league. Marshall says, “We’re winning the war…we won’t need the girls next year.”

Lowenstein responds, “This is what it’s going to be like in

the factories, too, I suppose…the men are back, Rosie, turn in your rivets. We told them it was their patriotic duty to

get out of the kitchen and go to work, and now when the men come back, we’ll

send them back to the kitchen?”

“There is no room for girls’ baseball in this country once

the war is over.”

The movie gives us plenty of action, to a swing and boogie

beat, and as the crowds get bigger, the stakes get higher.

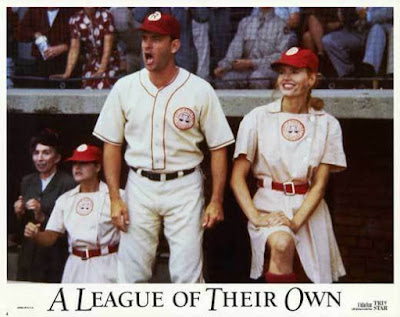

Tom Hanks plays the drunken manager, resentful at being forced to coach women, but by the end of the movie, he turns down a chance to coach Triple A to stay with his ladies. They have all traveled far. We almost gasp at the Hall of Fame scene to see his poster displayed with the date of his death. He won’t be coming to reunion, either.

Marla, played by Megan Cavanaugh, the unattractive introvert

who is the best hitter on the team transforms into a lovely young woman,

marries before the season is over, promises to return next season, married or

not, and we have the satisfaction of seeing her at the reunion enjoying an

apparently happy retirement.

We don’t know what happened to the longsuffering team

chaperone, Miss Cuthbert, played by Pauline Brailsford. I feel bad for her for the mean tricks and

insults she endured, but even she became one of the gang by the end.

Though I have read some reviews complaining of the modern-era bookends of the movie at the beginning and end, and the modern theme music played, particularly the one over the closing credits by Madonna, who plays “All the Way Mae,” as being a depressing closing to the film.

I disagree.

Above and below - Doubleday Field, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York (photos by JT Lynch)

The movie is about memory and

legacy as much as it is about action in the moment. It is not just a cute story about a novelty

female baseball team. There is always

some sadness in looking back, some sober reflection of how much age has changed

us and our world. We wish we could turn

the clock back, but then again, we don’t.

“This used to be my playground,” as the lyrics intone in a somber

refrain, is like a ghost telling us that the dream was not just a dream. We’re waking up much older in a different

reality. It really happened, but everything is changed

now and we can’t go back. We are

physically different, even if in our hearts we are still 20 years old.

It is delightful to see actual original players among the

elderly ladies playing baseball in their AAGPBL sweatshirts at the end of the

movie, the girls of October.

Penny Marshall gave us a chunk of history that was lost for a few decades and that is a great achievement. The movie itself is a cultural milestone. “That’s what makes it great” as Tom Hanks says of baseball, because it is hard.

Here is a link to the AAGPBL website with more information.

And here’s a link to members singing the team song you’ll remember from the movie.

Here's a link to the Women in Baseball exhibit at the Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Jacqueline T. Lynch is the author of Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. and Memories in Our Time - Hollywood Mirrors and Mimics the Twentieth Century. Her newspaper column on classic films, Silver Screen, Golden Memories is syndicated nationally. Her new book, a collection of posts from this blog - Hollywood Fights Fascism - is available here on Amazon.

No comments:

Post a Comment